The first part of the article is here.

Each enclave along the Armenian-Azerbaijani border has its own unique characteristics. Below, we present the specific issues related to each of them.

Verin Voskepar (Yukhari Askipara)

This was the largest former Azerbaijani enclave within Armenia, covering an area of 26 km², most of which is forested. Inside the enclave was a small Azerbaijani village of the same name, founded in the mid-19th century by settlers from several Azerbaijani villages in what is now the Gazakh district. By the late 1980s, the village had a population of approximately 500 people.

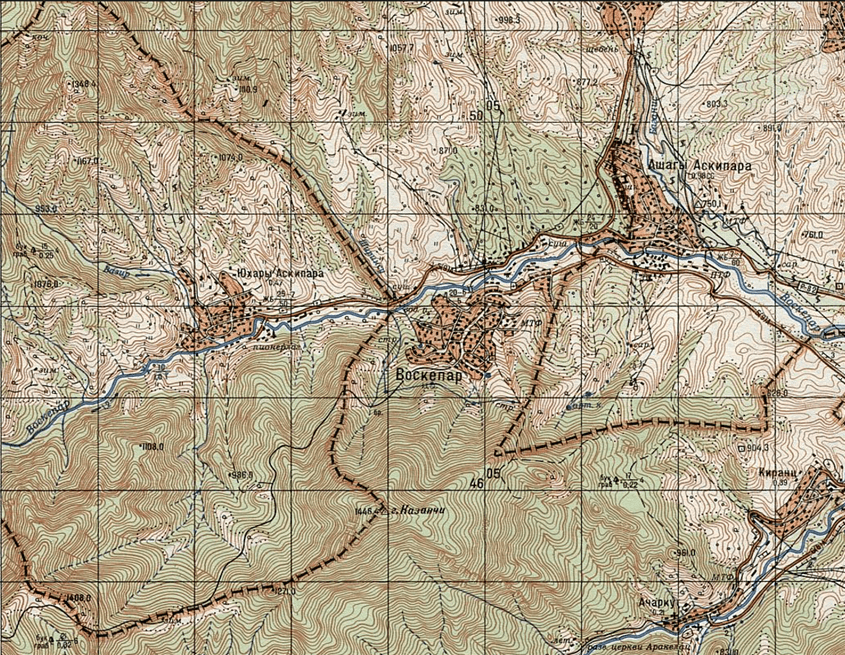

The return of this enclave to Azerbaijan would mainly create problems for the village of Voskepar, which would lose grazing lands appropriated within the enclave, part of its water resources, and the most convenient and shortest road to its mountainous pastures. If the so-called “Voskepar Triangle” is also restored to Soviet-era borders, the village would end up in a narrow corridor surrounded on two sides by Azerbaijani territory, creating significant obstacles to its normal functioning.

To the east of the enclave, but still within Armenian territory, runs the DN1000 gas pipeline that supplies Armenia from Georgia.

There have been frequent claims that a segment of the Armenia-Georgia interstate highway passes through the enclave, but this assertion does not reflect reality. Instead, four sections of this road (with a total length of approximately 1.9 km) pass through the “Voskepar Triangle.” Given that the Azerbaijani side does not appear interested in reclaiming the area north of the Berkaber Reservoir—evidenced by the fact that it bypassed this segment during the “delimitation of the four villages” process—it is likely that an exchange involving the “Voskepar Triangle” will take place. However, the land areas differ: the Armenian-controlled “triangle” north of the reservoir covers about 7–7.3 km² (including water surface), whereas the Azerbaijani enclave under Armenian control spans 4.5 km².

Despite this, the Armenian side should still consider at least alternative ground-based solutions for this section. A more expensive but long-term justified option would be constructing a roughly 3 km tunnel from the AcharKut village area to Voskepar. This would facilitate and accelerate traffic along the interstate road while also boosting the tourism potential of the Arakelots and Kirants monasteries, located above AcharKut. Notably, Arakelots Monastery was listed among Europe’s seven most endangered monuments in 2025.

Another claim—that the enclave’s western border aligns with the mountain range separating Lori and Tavush provinces, including its main peaks—is also a distortion of reality. The enclave is entirely located on the eastern slopes of the Gugark mountain range, lying below the dominant watershed peaks of the range, which remain entirely within Armenian territory.

Map 1: Voskepar Village Between the Verin Voskepar Enclave and the “Triangle” Based on Soviet-era Administrative Borders

Sofulu-Barxudarli

This enclave is located in the Aghstev River valley and presents the most complex infrastructural challenges. The enclave covers an area of 9.87 km². During the Soviet era, the Ijevan-Gazakh highway and railway passed through this enclave, as well as the main highway connecting the Ijevan and Berd regions (although an alternative route is now available).

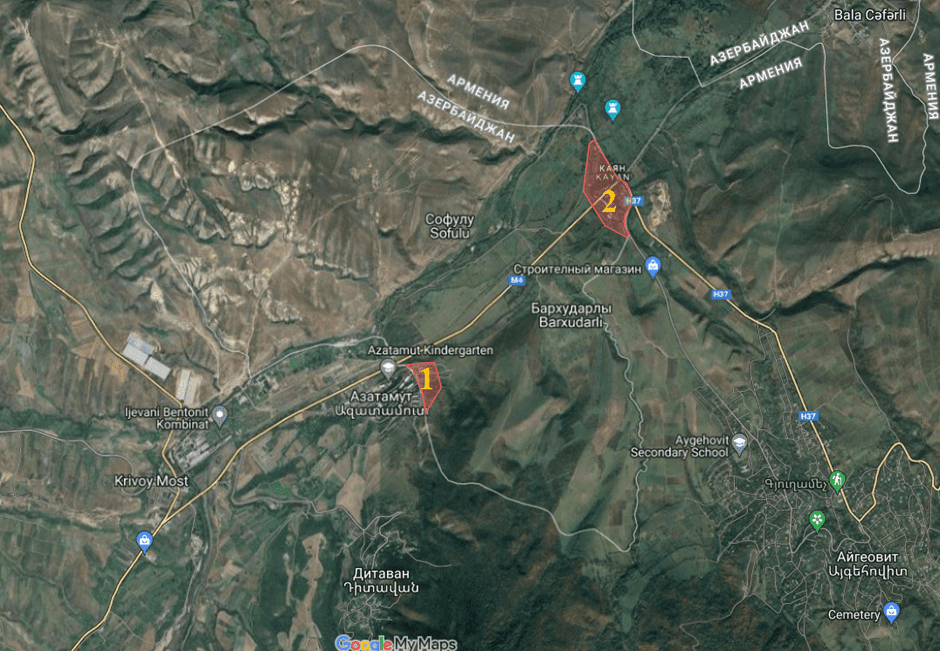

At the same time, the enclave includes the settlement of Kayan, which was built adjacent to the Kayan railway station during the Soviet period, as well as part of the residential and infrastructure area of Azatamut, constructed near the “Bentonit” factory. This enclave is perhaps one of the best examples of the complexity of Soviet administrative borders and policies: within an enclave belonging to Soviet Azerbaijan but located inside the Armenian SSR, there were two Azerbaijani villages (Sofulu and Barxudarli), an Armenian settlement (Kayan), and part of another Armenian settlement (Azatamut).

Map 2: Armenian Residential Areas Within the Sofulu-Barxudarli Enclave – Part of Azatamut (1) and Kayan Settlement (2)

If the enclave is returned to Azerbaijan, the agreed-upon regulation between the parties, which aims to optimize the border according to the needs of border settlements, stipulates that the territory belonging to Kayan and Azatamut (approximately 25 hectares or 0.25 km²) should be excluded from the enclave and remain under Armenian jurisdiction.

Additionally, if the enclave is returned, the section of the Ijevan-Berd highway that currently runs through it would need to be rerouted via an alternative route—following the Ditavan-Aygehovit line. Importantly, this bypass route would not be significantly longer than the current one (approximately 7.5 km). The alternative road would also pass near the medieval Srvegh Monastery, which has the potential to become a significant tourist destination.

Tigranashen (Kyarki)

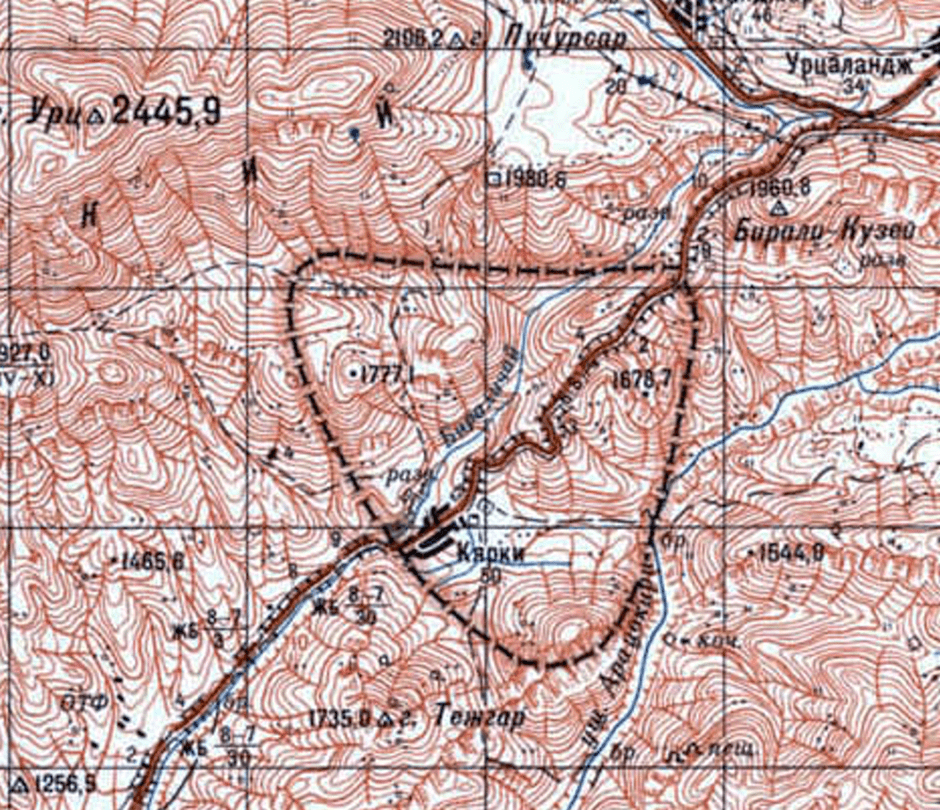

Tigranashen is the smallest of all the enclaves, covering an area of 8.13 km², predominantly arid, rocky, and devoid of vegetation. A 4.5 km section of the M-2 Armenia-Iran interstate highway (constructed in the 1960s) runs through the enclave.

Among all the former enclaved settlements, this is the only one that remains inhabited, primarily by Armenian refugees from various regions of Azerbaijan. One of the reasons for this is that it came under Armenian control in January 1990, when the hostilities were mostly limited to small arms fire, and as a result, the housing stock did not suffer as much damage as during the later military operations of 1992-1994.

The Biralichay stream flows through the enclave, although it dries up in the summer. Its upper course lies within Armenian-controlled territory, meaning that even if water is present, its management can remain under Armenia’s jurisdiction. The severe shortage of independent water resources is expected to be one of the enclave’s most critical challenges if it is returned to Azerbaijan. It would be entirely dependent on external supplies and infrastructure, which would need to pass through Armenian territory.

Map 3: Kyarki (Tigranashen) According to the 1981 Soviet Army General Staff Map

While it is often stated that the M-2 interstate highway running through the enclave is the only route connecting Armenia to Syunik and Iran, there are two additional paved roads: the Vedi-Lanjarr route (43 km, which is challenging for heavy trucks) and the M-10 Sevan-Martuni-Vayots Dzor interstate road.

Under the North-South Transport Corridor project, the planned highway is expected to bypass the enclave. Therefore, the current strategic significance of the road passing through the enclave is temporary, and claims regarding its importance are often exaggerated. Since any bypass route would have to traverse more complex terrain, requiring tunnels and viaducts, the most viable solution would be to expedite the construction of the Zovashen-Surenavan section of the North-South Highway, ensuring a long-term transportation solution.

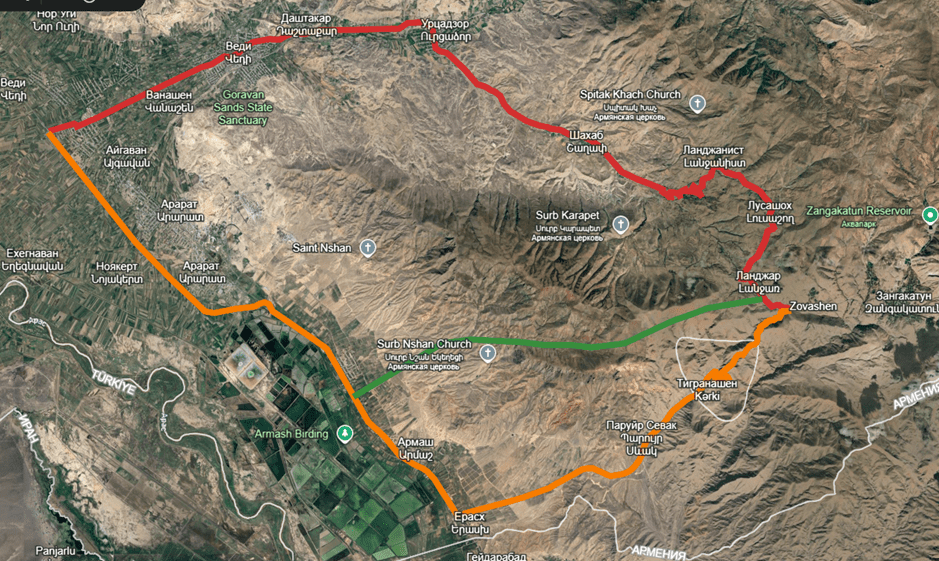

Map 4: Transportation Links in the Tigranashen Area

🟥 Vedi-Lanjarr road–43 km

🟧 The same route passing through Tigranashen – 43.5 km

🟩 Potential bypass section of the North-South Highway

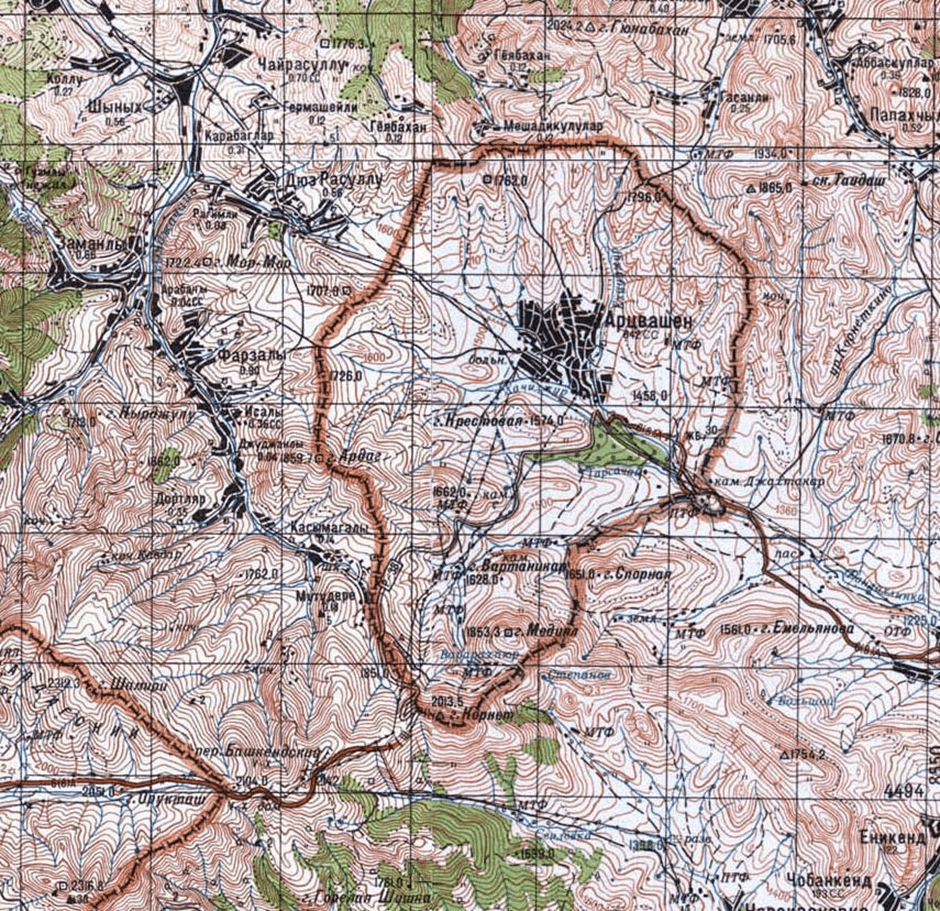

Artsvashen

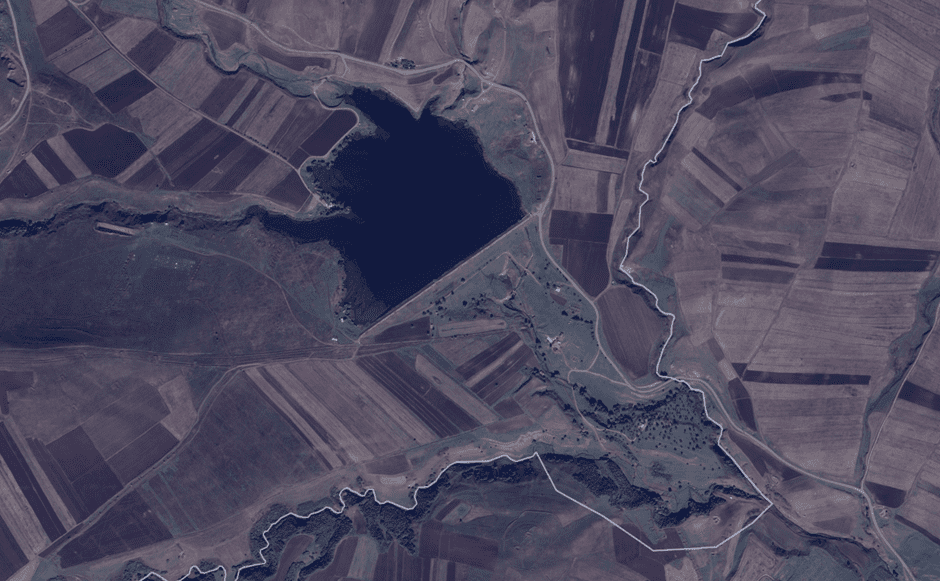

Artsvashen is the largest of all the enclaves, both in terms of territory and former population. The area is rich in pastures, which are currently used by residents of neighboring Azerbaijani villages, as well as water resources, including numerous rivers and springs (at least 23) that are part of the Khachijur River basin. In the southwestern part of the enclave, there is also a reservoir constructed by Azerbaijan following its occupation of the area—an indicator of the enclave’s critical importance for Azerbaijan’s water management.

Map 5: The Reservoir Built in the Southeastern Part of Artsvashen

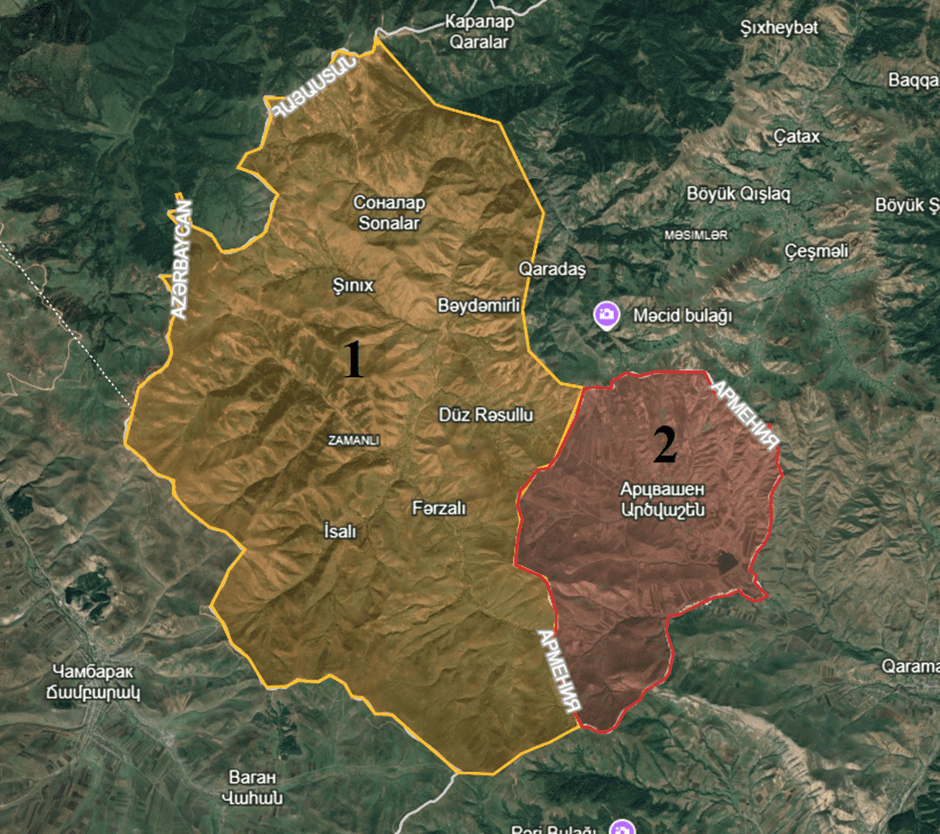

A key transportation route runs through Artsvashen, serving as the only functional road connecting 26 villages in the Shamkhor-Ayrum subdistrict of Azerbaijan’s Gadabay region (with a total population of 10,000-12,000 and an area of approximately 130-140 km²) to the district center. Neighboring villages in the Tovuz region also rely on this route. Alternative bypass roads are significantly less convenient, traversing extremely mountainous terrain. The semi-blockaded status of these Azerbaijani villages was a major factor in the participation of their residents in the military assault on Artsvashen on August 8, 1992.

Map 6: The Shınık-Ayrum Subdistrict (1) of Gadabay Region, Whose Connection to the District Center Would Be Cut Off if Artsvashen (2) Were Returned to Armenia

Azerbaijani sources frequently claim that the enclave is approximately 30 km away from Armenia. However, the actual distance is 3.3 km in a straight line and 3.9 km via the former highway.

Map 7: Artsvashen According to the 1988 Soviet Army General Staff Map

While Azerbaijan’s official rhetoric and analytical discourse assert that, unlike the Azerbaijani enclaves within Armenia, Artsvashen lacks strategic significance, the residents of neighboring Azerbaijani villages strongly oppose its return to Armenia. Azerbaijani-language publications themselves acknowledge the enclave’s strategic location, its commanding heights overlooking the adjacent subdistrict, and its agricultural importance.

Potential Solutions Regarding the Enclaves

Although returning the enclaves to the respective sides based on their Soviet-era administrative affiliation is one possible resolution—one that Armenia should also be prepared for—such an approach would pose numerous challenges. Given that the Armenia-Azerbaijan borders are no longer merely administrative but state borders, this solution would create significant complications for both the residents currently settled in the enclaves and those in the surrounding areas, including infrastructure and communications.

Since the former inhabitants of the enclaves resettled in other parts of their respective “mother” countries after 1990-1992 and have already adapted to new living conditions, only a small fraction—primarily the older generation—would likely wish to return. Over time, this would result in nearly uninhabited and costly-to-maintain areas, where the primary residents would be border guards. Additionally, all infrastructure supplying the enclaves would have to pass through the neighboring country’s territory, making construction, maintenance, and repairs a legally and logistically complex process. For enclaves with small populations, access to medical, administrative, and other essential services would also be a serious concern.

A more viable solution under current circumstances would be to formalize the existing territorial exchanges at the conclusion of the border delimitation process. This would remove the enclave issue from the broader negotiation framework, alongside other exchanged areas, including the so-called “triangles” and other sections.

The discrepancy in land area between Artsvashen and the Azerbaijani enclaves (approximately 6 km²) could be compensated through territorial swaps near Voskepar, where Armenia’s “triangle” is about 2-2.5 km² larger than Azerbaijan’s, as well as in the Vazashen and Paravakar areas. These regions, currently under Azerbaijani occupation, could be transferred to Azerbaijan, allowing their villages (Bala Jafarli, Tatli, Kyohnagshlagh) to be directly connected to the “mother country.”

At the same time, since Azerbaijan has been leveraging the enclave issue and its associated infrastructure as a political tool to extract disproportionate concessions from Armenia (despite its own lack of genuine interest in regaining Artsvashen), Armenia must take proactive measures to secure its own infrastructure and communications passing through the enclaves. This would effectively neutralize Azerbaijan’s ability to use the issue as a means of coercion. It is crucial that these points are reflected in Armenia’s official and public discourse.

Samvel Meliksetyan