On August 30, 2024, with a two-month delay from the date mentioned in the April 19 announcement, the regulation for the delimitation of the Armenian-Azerbaijani border was signed. I have tried to propose three main explanatory models for the significance of the regulation in the context of the Azerbaijani side’s political strategy.

Model 1

Azerbaijan is buying time postponing the process of relations settlement. On the eve of COP29, Azerbaijan is interested in presenting itself as a constructive party, which is why it is proceeding with the signing of the delimitation regulation, which contains points subject to contradictory conclusions that allow for almost endless postponement of this process as well. Azerbaijan’s imitative activity around the peace treaty is aimed at convincing the international community but the Azerbaijani side’s main goal remains to achieve its objectives through military means if possible, including resolving the so-called “Zangezur corridor” issue. Facing some pressure from the West and seeing Armenia’s intensifying political and military-technical ties with Western countries, Azerbaijan is beginning to view Russia as an important factor that can balance this pressure. Azerbaijan does not have similar concerns about Russia and considers it important to use its ties with the Russian side to increase pressure on Armenia. The option of a “corridor” under Russian control may be acceptable to Azerbaijan under certain conditions.

Model 2

The Azerbaijani side’s goal is indeed the final settlement of relations and establishment of peace. The signing of the regulation ahead of COP29 by Azerbaijan is both a positive signal to external parties and a positive scenario in the track of the peace treaty, a certain concession by which they are trying to incentivize Armenia, expecting concessions on other issues to the Azerbaijani side. The Azerbaijani side is using its military and resource advantage over Armenia, as well as taking advantage of the opportunities created by the Russia-West conflict. Under these conditions, it will continue its pressure on the Armenian side, expecting a settlement of relations on terms most favorable to itself. At the same time, it does not have the old motivation and real goals to go for medium or high-intensity military escalation. In the long-term perspective, the Azerbaijani side does not trust the Russian side and its long-term policy goals in the region are to weaken the Russian positions. Nevertheless, while continuing to have concerns about Russia, the Azerbaijani side does not take bold steps against it as long as the results of the Ukrainian war are unclear. However, being confident that the Armenian side will not agree to the Russian side’s mediation offer, it shows solidarity with the latter with the intention of putting additional pressure on Armenia. This approach can be characterized as a scenario for normalizing relations with Armenia at the cost of maximum possible concessions from Armenia.

Model 3

The Azerbaijani side does not have the rigid limitations described in the first two models. Depending on the development of the international and negotiation situation, it is ready to drastically change the nature of both its external relations (with Russia or the West) and the toolkit used (military, diplomatic, negotiation). The regulation is one of the means that allows for such a flexible policy: depending on the situation, issues and processes related to the content of the regulation can be frozen, postponed, revised, or quite the opposite, develop quickly in a constructive direction.

Among the three models mentioned, I am inclined towards the second and the third. This uncertainty is related to the sensitivity of conflict resolution, dependence on international developments, and the activity and determination of various external actors (including mediators). The choice of the second option is also conditioned by the agreement of bilateral decisions (removal of the communications unblocking point from the treaty) that, at least temporarily, hinder Russian mediation on this issue. The other reason (below) is the content of the regulation, where the Azerbaijani side has an obvious interest in practical solutions based on these principles and does not view it as purely imitative.

THE CONTENT OF THE REGULATION

Moving on to the actual content of the regulation, I consider it important to highlight several issues:

1. Languages: The regulation was signed in three languages – Armenian, Azerbaijani, and Russian. Although opinions were expressed that the latter fact is a political reverence to the Russian side, I think the reason is much simpler – the absence of appropriate and clearly formed professional terms related to the process in Armenian and Azerbaijani, as almost all existing legal and cartographic material is also in Russian, which is understandable to the members of both sides’ commissions. This decision was, first of all, technical. It should be noted that the OSCE work guide was also published only in Russian and English versions.

2. The mention of the 1991 Alma-Ata Declaration in the preamble, but the absence of a reference to a specific map: The 1991 Alma-Ata Declaration serves as the basis for recognizing the succession of post-Soviet republics, maintaining the borders of the former Soviet republics and their territorial integrity. It is not necessary to specify a precise map in the regulation because in all such cases, the administrative boundary that was legally justified on the eve of the collapse of the USSR (i.e., based on the same maps from the 1970s) is recognized as the basis for the border.

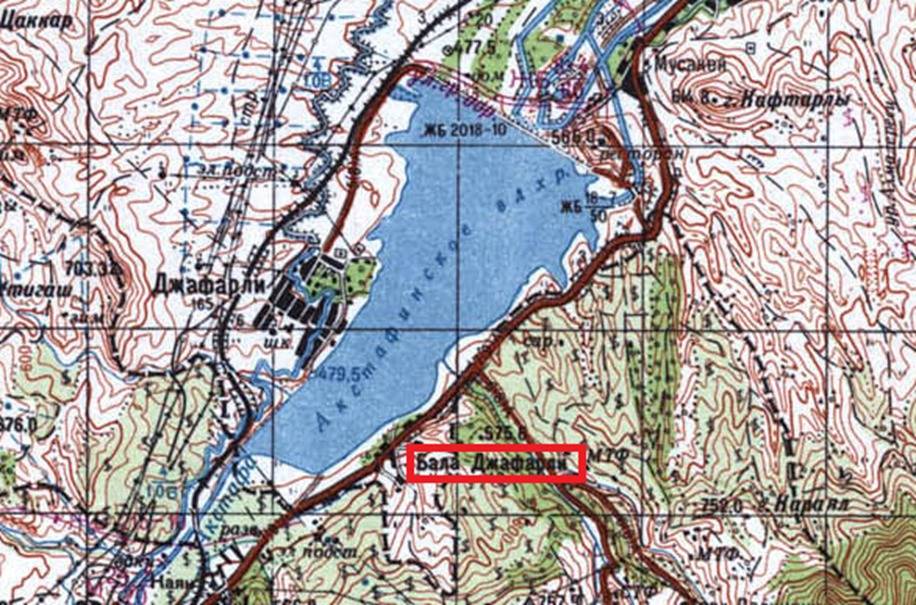

3. Since the point about border optimization (Article 4 in its entirety) is included in the regulation, this document almost completely replicates the OSCE-published guidebook on delimitation and demarcation[i], both in this matter and in others. During the so-called “four villages” process, ignoring optimization as one of the key principles of the mentioned OSCE guidebook created numerous problems related to housing stock, infrastructure, and traditional land use practices in the Kirants village area of Armenia’s Tavush region. In my conviction, the Azerbaijani side’s decision to change its approach and recognize such a principle was conditioned by the fact that, as I have mentioned in my previous publications[ii], a mechanical return to the late Soviet-era borders would create many problems primarily for several Azerbaijani villages adjacent to Armenia’s Tavush region, including more complex ones than in the case of Kirants. Some of these villages may lose their transport connections (Bala Jafarli, Lower Askipara, Baghanis Ayrum, Kheyrımli, Gushchu Ayrum, etc.), housing stock (Tatlu, Yaradullu, Alibeyli, Aghdam, etc.), and land resources (some of the mentioned villages, Kemerli, Gaymakhli villages). The same principle allows the Armenian side to raise the issue of border optimization in the Goris-Kapan road section.

Map 1. The Azerbaijani village of Bala Jafarli adjacent to Tavush that will lose its connection to the country if returns to Soviet-era borders.

5. In my opinion, the section about possible changes to regulations in the preamble and Article 6 of the regulation refers to potential territorial exchanges in the case of so-called “triangles,” “tongues” (e.g., south of Nerkin Khndzoresk village), as well as enclaves. Such ambiguity, of course, also allows understanding how to include possible optimal solutions in the future that may arise at different stages of the process, as well as make the exchange of the same enclaves or other territories a subject of sale according to political developments. Almost all articles mentioned in the regulation, as we have noted, are brief reproductions of the content of the OSCE guidebook. It should be noted that the formation of commissions mentioned in the regulation (Articles 1 and 3) and the technical requirements (creation of a topographic map reflecting the current situation of the area) require some time before proceeding to the actual process. The subsequent actual delimitation process, in turn, can continue for years, given the length of the Armenian-Azerbaijani border (about 1000 km) and the complexity of the issues. In this regard, although this process can be a positive signal for an overall political settlement, it is not an independent political driver and significantly depends on other elements of the Armenian-Azerbaijani settlement, which can be a serious obstacle or stimulus to the delimitation process.

Summary

The regulation was signed against the backdrop of certain positive and negative trends in the process of normalizing Armenian-Azerbaijani relations. We believe that crisis tendencies are predominant. However, it should be noted that it is characteristic of Azerbaijani official tactics to toughen rhetoric against the background of important practical agreements.

In terms of content, the regulation almost literally follows the recommendations of the document-guideline published by the OSCE. Such a change in principles instead of the logic of the “four villages” process, in my opinion, is due to the fact that if continued with that logic, the Azerbaijani villages adjacent to Tavush would have been significantly affected first. The fact that Azerbaijan has nevertheless agreed to apply more optimal principles based on the interests of the border zone population also shows that the Azerbaijani side does not view this process as merely imitative.

[i] https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/9/2/363466.pdf

[ii] https://www.ypc.am/lineofcontact/2024/08/02-08-2024-ru/?fbclid=IwY2xjawFZGH9leHRuA2FlbQIxMQABHTBcHYXxOJQ8aPlSxlyB1DChVX4tvSDF6uGE4j0UwekdZG0qroTZlLT4LQ_aem_38yRQsEgePz4dHVTNbYsVg

Author: RCSP associate expert Samvel Meliksetyan