In the context of the Middle Corridor, priority is given to rail transportation. In my previous article, I proposed the shortest route of the Middle Corridor through the South Caucasus—Kars–Vanadzor–Ijevan–Qazakh–Baku—which can be made operational with the construction of a short segment (Vanadzor–Fioletovo, approximately 30 km) and the restoration of the Dilijan–Armenia border section (68 km). In this article, I present additional arguments in support of this proposed rout.

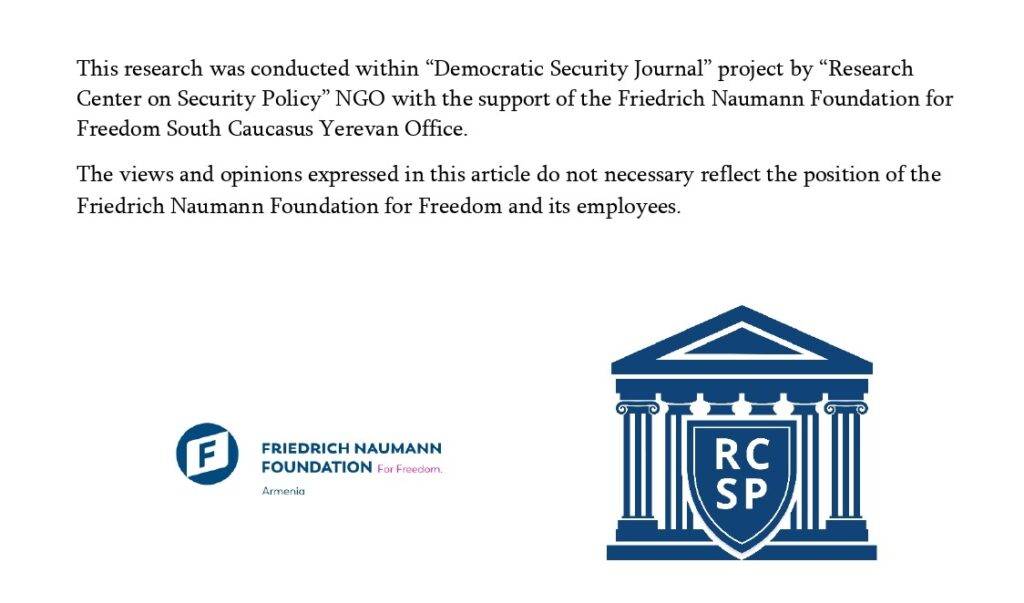

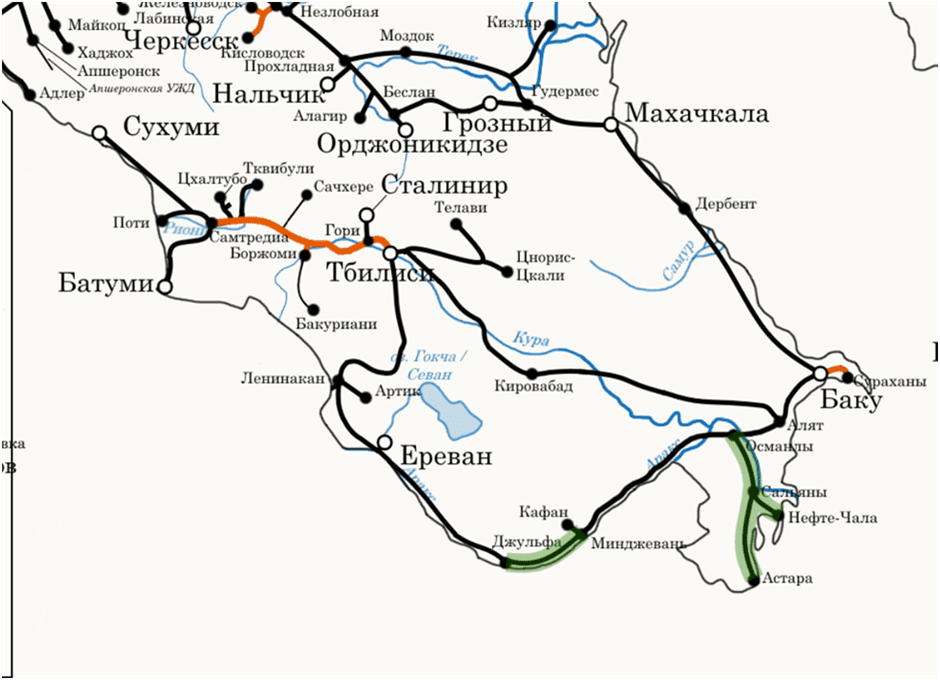

Map 1: Railway lines in the Caucasus region in the 1870s

Formation and Logic of the South Caucasus Communication Network

The formation of the modern communication network in the South Caucasus began in the second half of the 19th century, during the period of the Russian Empire, primarily through the construction of railway infrastructure. In 1872, the Poti–Tbilisi railway was built, connecting the Black Sea to Tbilisi, and by 1883 it had been extended to Baku.

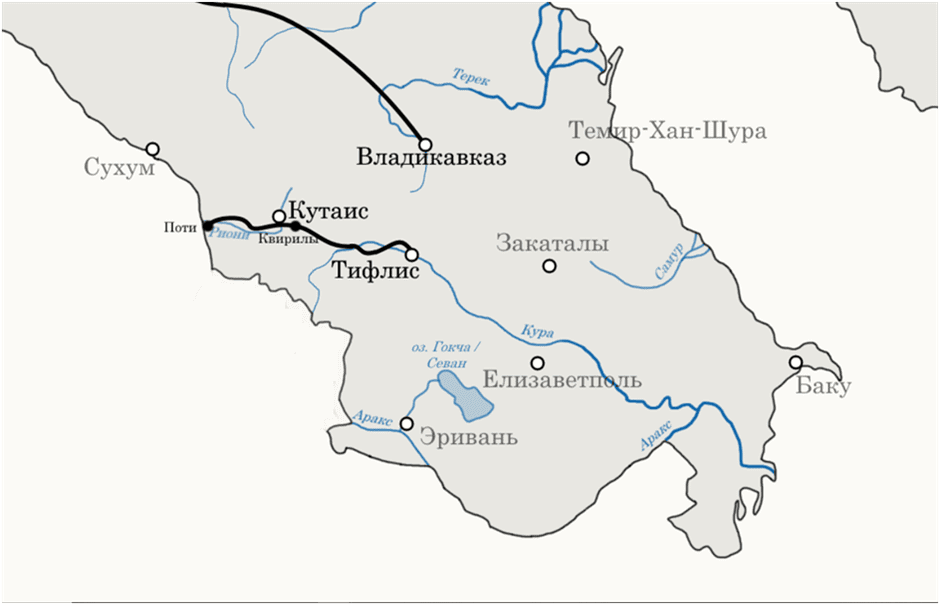

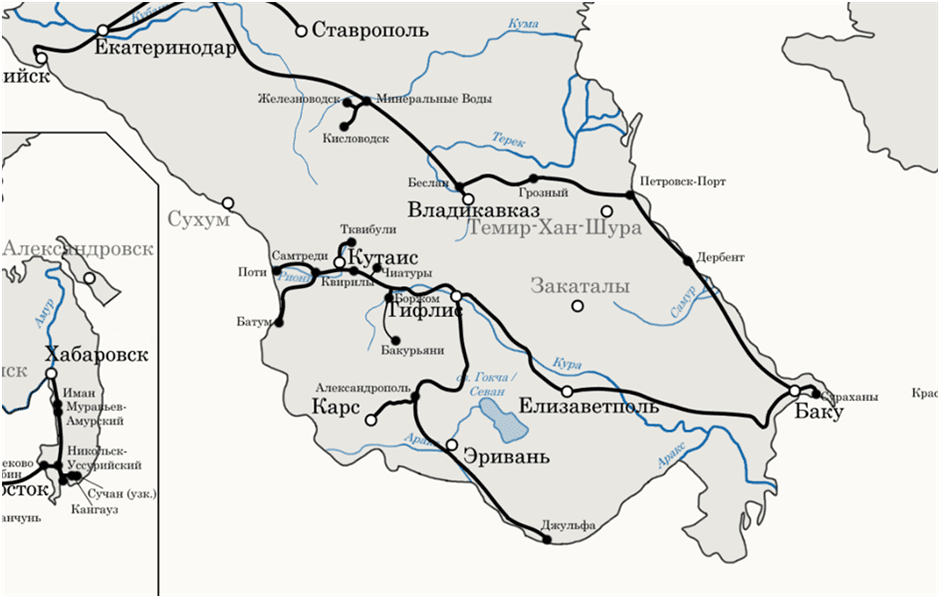

This infrastructure development primarily served administrative goals—governance of the region and strengthening ties with central Russia—as well as economic aims, such as transporting Baku’s oil to Black Sea ports and inland Russia. By 1900, a railway line along the western Caspian coast connected Baku to the transportation network of southern Russia through the Baku–Derbent–Petrovsk (Makhachkala) line. Starting from the late 19th century, railway construction also began serving new objectives—military and colonial in nature. In 1895, the Russian Empire initiated the construction of the Tbilisi–Alexandropol–Kars and Alexandropol–Yerevan–Julfa railway lines, intended to bring infrastructure closer to the borders of the Ottoman Empire and Persia and to stimulate future military and economic activity in those directions. After the signing of the Anglo-Russian Convention in 1907, which divided Persia into spheres of influence between the two empires, the Russians continued railway construction within Persian territory, reaching from Julfa to Tabriz by 1915.

Map 2: Railway lines in the Caucasus region in the 1880s

Map 3: Railway lines in the Caucasus region in 1908[1]

During the Soviet era, large-scale railway construction continued, maintaining the aim of strengthening connections

with the center and serving geostrategic objectives. These efforts largely followed a north–south axis and intensified particularly during the 1930s and World War II. Parallel to the 1941 occupation of northern Iran, the Julfa–Baku railway line was completed along the Araks River (Ordubad–Meghri–Midjnavan), and both Julfa and the earlier Russian-built line toward Tabriz became principal routes for Soviet military buildup and the launching of the offensive into Iran in August–September 1941. The Baku–Julfa line became a key route for the Lend-Lease program—approximately 34% of the total U.S. supplies to the USSR passed through Iran—and it emerged as the primary connection between the USSR and northern Iran. It later became the basis for Azerbaijan’s current so-called “Zangezur Corridor” concept. Following the same logic, in 1941, the Baku–Astara line reaching Iran’s northern border along the western coast of the Caspian Sea was also completed.

Map 4: Railways of Soviet Transcaucasia in 1941(The Julfa–Midjnavan and Osmanly–Astara railway lines, commissioned in 1941, are marked in green.)[2]

In the post-war period, a more important factor was the construction of communications infrastructure serving inter-republican connections and economic needs. During this period, the construction of the Ijevan–Aghstafa railway line in 1973 was especially significant for Armenia’s external connectivity. This route was extended toward Dilijan–Fioletovo–Hrazdan–Yerevan, completed in 1985. The Pambak railway tunnel—at 8,311 meters, the third longest in the USSR—was built along this section.

The full utilization of this railway, hindered by the collapse of the Soviet Union, was intended to ensure faster and more efficient connections from Yerevan to Baku and Tbilisi via the Ijevan–Qazakh–Baku and Ijevan–Qazakh–Tbilisi routes, as opposed to the longer and less convenient Yerevan–Gyumri–Tbilisi and Yerevan–Nakhijevan–Meghri–Baku lines.

Map 5: Railway networks of Soviet Armenia and Azerbaijan in 1990[3]

Following Armenia’s independence, the idea of connecting the Tbilisi–Vanadzor–Gyumri–(Kars) railway (operating since the Tsarist period) with the newly constructed Yerevan–Ijevan–Qazakh railway via the Fioletovo–Vanadzor segment (estimated at 25–32 km, depending on the project) was discussed several times. Such a connection would make internal Armenian rail transport and the Yerevan–Tbilisi route significantly more efficient.

The construction of the Vanadzor–Fioletovo section was also envisioned by the Russian railway company (RZD) as part of the 2008 concession agreement establishing “South Caucasus Railways,” under which the company took over the management of Armenia’s rail network.

The collapse of the USSR in 1992–93 resulted in the blockade or semi-blockade of several critical routes in the region. The railway connection between Armenia and Azerbaijan was shut down in the Nakhijevan and Ijevan sections. In 1993, the Abkhazian railway—Armenia’s shortest and most convenient link to Russia—was also closed, along with the Baku–Julfa–Iran railway and several road connections.

In the early 2000s, Azerbaijan and Georgia launched the construction of multiple energy and transport infrastructures connecting to Turkey and Black Sea ports. One of these was the Baku–Tbilisi–Kars railway, deliberately bypassing Armenia.

Thus, while the main motivation for railway construction during the Tsarist and Soviet periods was regional integration with the center and the fulfillment of Moscow’s geopolitical objectives, the main trend in the post-Soviet period has been the development of communications infrastructure that bypasses Armenia. In both cases, the logic of developing optimal East–West communication routes in the region has remained absent.

The Impact of the Armenian–Azerbaijani Conflict and Its Resulting Communication Arrangements on the Middle Corridor Project

As previously noted, existing railway communications in the South Caucasus were either constructed in the context of the Russian Empire’s and Soviet Union’s military-political and broader economic interests, or—after the collapse of the USSR—based on a rationale of bypassing Armenia while enhancing connectivity among Turkey, Georgia, and Azerbaijan. Since Armenia lies on the same geographic latitude as Baku and Kars—two of the region’s principal railway hubs—all functioning communication lines linking those cities are longer than the potential routes passing through Armenian territory. Therefore, both the Soviet-era infrastructure and the post-Soviet bypass routes diminish overall efficiency along the East–West axis.

Another manifestation of the Soviet legacy is the railway track gauge of 1520 mm, in contrast to the European standard of 1435 mm (also used in Turkey).

On the Kars–Akhalkalaki line, a gauge-change facility operates at the Akhalkalaki station to switch from the Russian 1520 mm to the European 1435 mm standard. While this transition slows freight movement to some extent, it is technically feasible and continuously improving. Should Armenia’s railway network be connected, this gauge-change operation could be performed in Gyumri by constructing a major freight terminal within the framework of a dry port concept. The wheelset conversion could occur either at the border or in Gyumri itself—assuming a 1435 mm European-standard railway is extended from the Turkish border to Gyumri.

Another key issue is that the current communication proposals maintain the logic and objectives shaped during the conflict period. This is evident in the tendency to minimize Armenia’s potential benefits from these projects, even at the cost of undermining the overall optimization of the transportation routes.

For example, the issue of simplified or unimpeded connectivity with Nakhijevan—often politicized as the so-called “Zangezur Corridor”—is presented in Azerbaijan as a regional optimization solution. Within the context of the Middle Corridor project, this leads to an overestimation of the importance of the railway line passing through Nakhijevan, while overlooking the multiple risks and deficiencies associated with it.

Conversely, this same post-conflict inertia has led to efforts to develop an alternative northern route bypassing Armenia via Georgia. Yet these options are economically less efficient when compared to several other potential transportation scenarios that involve Armenia.

Below are several arguments illustrating the advantages of the route passing north through Armenia, especially when compared with competing alternatives.

The Geographical Factor

The currently operational Baku–Tbilisi–Kars corridor, which bypasses Armenia by deviating northward, is longer than a potential route that would traverse northern Armenia—namely, the Kars–Gyumri–Vanadzor–Ijevan–Qazakh–Baku line.

As previously mentioned, to operationalize this route, approximately 25–32 km of new construction is required in the Vanadzor–Fioletovo section, along with the rehabilitation of around 81 km of railway in the Fioletovo–Qazakh stretch (68 km of which lies within Armenian territory).

In comparison with the existing Kars–Tbilisi–Baku railway, the proposed route follows a gentler incline, ascending toward the Kars plateau, and therefore offers higher potential capacity.

The total length of the Kars–Tbilisi–Baku route is 825 km. The proposed Kars–Gyumri–Vanadzor–Qazakh–Baku corridor is 718 km long (and could be shortened by an additional 10–15 km with the construction of a few new tunnels and segments). By contrast, the so-called “Zangezur Corridor,” which follows the Kars–Nakhchivan–Meghri–Baku line, measures 863 km in length.

Thus, the route through northern Armenia is 107 km shorter than the northern corridor and 145 km shorter than the Meghri-based “Zangezur Corridor.”

Projected Freight Volume on the Middle Corridor and Its Impact on Route Optimization

Following modernization efforts in 2024, the annual capacity of the Baku–Tbilisi–Kars railway increased from 1 million to 5 million tons, which currently satisfies the needs of the Middle Corridor (in 2024, the cargo volume transported along the Corridor reached 4.5 million tons[4]).

By 2027, the projected freight volume on the Middle Corridor is expected to reach 10 million tons, and by 2030—11 million tons. Importantly, most of this volume is not China–Europe transit, but rather intra-regional trade among participating countries (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkey[5]).

Azerbaijani forecasts suggest that if the so-called “Zangezur Corridor” is opened, the total volume of freight transported along the Middle Corridor could rise to 8–10 million tons[6].

Therefore, even if both routes—Kars–Tbilisi–Baku and Kars–Nakhijevan–Meghri–Baku—are operational and function simultaneously, they will soon reach their full capacity and will not sufficiently accommodate growing East–West demand.

Moreover, since both routes are longer than the northern Armenian alternative, reaching the same freight volumes would entail financial losses amounting to tens of millions of US dollars.

At the same time, the implementation of Middle Corridor-related communication infrastructure projects is expected to exceed the capacity of the currently planned routes in the medium term.

The primary receiving port of the Middle Corridor in the South Caucasus—Alyat, located in Azerbaijan—is scheduled for modernization, with its handling capacity projected to increase from 15 million to 25 million tons of cargo annually[7].

In Central Asia, Kazakhstan is expected to complete the construction of the Bakhty–Ayagoz railway by 2027. This development will enable an increase in freight volumes between China and Kazakhstan, expanding current capacity from 28 million to 48 million tons per year[8].

Another significant project—the Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan–China railway—is projected to have an annual capacity of approximately 12 million tons. Construction is planned to commence in July 2025 and conclude by 2031[9]. This route, too, is anticipated to become one of the partially servicing lines of the Middle Corridor.

Thus, the total annual freight capacity entering from Central Asia—particularly from China—may reach approximately 60 million tons over the next decade. While a portion of these shipments may transit through Russia or head south via Iran (supported by the Kazakhstan–Turkmenistan–Iran railway operational since 2014), a significant segment of cargo destined for Western markets via Iran is also expected to add substantial pressure to the Julfa–Nakhichevan rail segment. This corridor presently offers the most viable route to Black Sea ports and to Turkey.

The only competing and currently functional Iran–Turkey railway faces considerable capacity limitations due to the ferry-based crossing over Lake Van.

The resolution of international conflicts involving Iran and Russia, as well as the opening of alternative regional corridors (e.g., the Abkhazian railway or south–north connections from India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan via Iran toward Europe, Russia, and Turkey), will further intensify freight traffic, particularly on the North–South rail axis of the South Caucasus.

Currently, the only land-based railway link between Russia and Iran passes through the South Caucasus via the Julfa section in Nakhijevan. It is also the sole corridor in the region that connects the railway networks of Iran, Russia, and Turkey by land.

As these volumes grow, the Julfa section will experience increasing pressure, partially consuming the capacity of the so-called “Zangezur route.”

It is worth noting that Turkey views the railway connecting Nakhijevan to Iran as an opportunity to gain direct access to the Persian Gulf, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. Conversely, for Iran, this same route serves as the most viable existing railway access to the Black Sea ports and Europe.

Therefore, both Iran and Turkey are interested in utilizing the Nakhijevan route for their own strategic purposes, which will considerably reduce the available capacity of the so-called “Zangezur route” for East–West transit (i.e., Kazakhstan/Turkmenistan–Caspian Sea–Baku–Nakhijevan).

Geopolitical Factor

The so-called “Zangezur Corridor” railway route running through southern Armenia spans approximately 360 km, with much of it lying along the left bank of the Araks River—forming the border between Armenia and Iran, and partly between Azerbaijan and Iran. In certain segments, this railway route approaches as close as 10 to 30 meters from the Iranian border.

Meanwhile, major transport infrastructure in central Georgia—including the railway to the Black Sea and the E60 highway—passes near the occupation line of Russian-controlled South Ossetia, at distances of 8.7 km and just 350 meters, respectively.

Given the heightened geopolitical risks and the potential for internal instability in both Russia and Iran—including uncertainties around regime transitions, the presence of political radical movements and separatist sentiments among Muslim populations in the North Caucasus, as well as ethnic and religious tensions within Iran—these routes may involve additional vulnerabilities.

Russia and Iran may perceive these transport corridors as bypassing their territories and strengthening economic ties among competing regional actors. For Russia, in particular, these routes could undermine its strategic influence over Central Asia and the South Caucasus.

From a security standpoint, the most stable and secure corridors are those running through the central part of the South Caucasus.

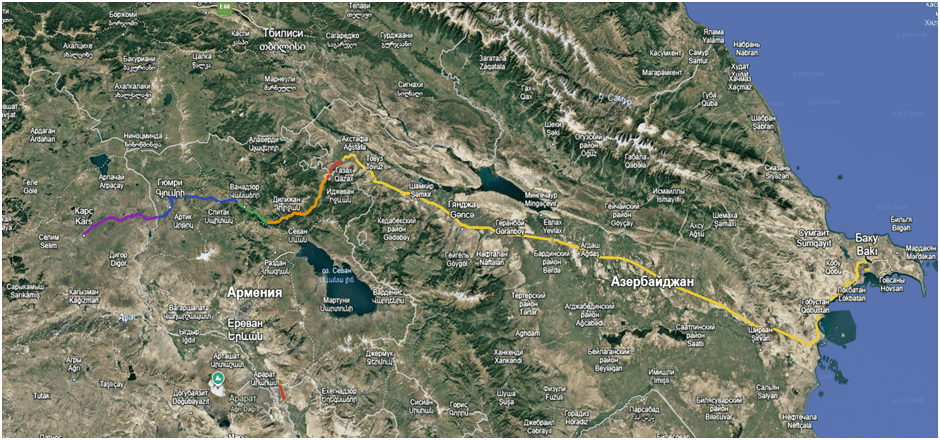

Map 6. Proposed Kars–Gyumri–Vanadzor–Ijevan–Gazakh–Baku Railway Route. The Vanadzor–Fioletovo segment requiring construction is marked in green[10].

Map 7․ Comparative visualization of the northern Armenia railway alternative versus the existing Kars–Akhalkalaki–Tbilisi–Baku and Kars–Nakhijevan–Baku routes.

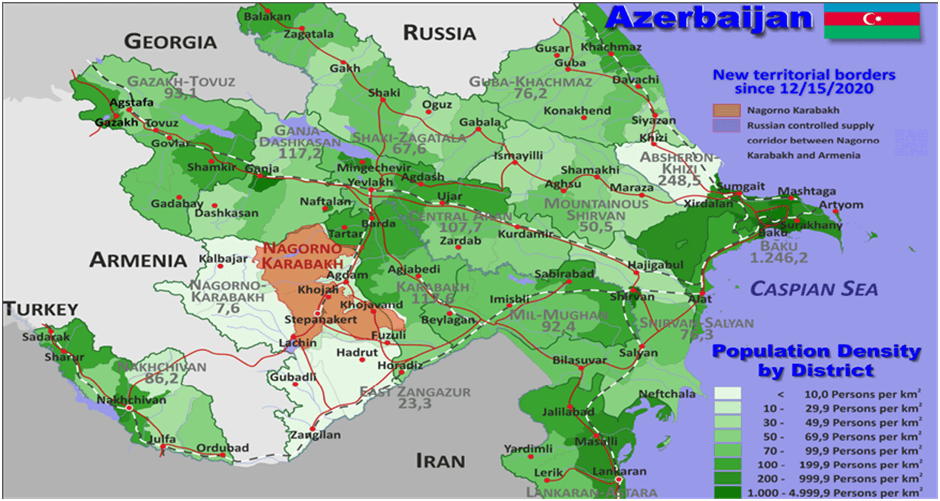

Demographic Factor

The so-called “Zangezur Corridor” route, which passes through the territories of Armenia and Azerbaijan, traverses largely uninhabited or sparsely populated areas. Much of the route lies along the southern border of the two countries with Iran and is geographically isolated by various natural barriers (arid steppes, mountain ranges, etc.). On the Azerbaijani side, a largely uninhabited mountainous steppe area stretches from the settlement of Bahmanli in the north to the Armenian border in the west. Similarly, in the territory of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic, the railway is bordered by sparsely populated mountainous zones, further isolating it from the densely populated areas of the Karabakh plain. Along this route in Azerbaijan, relatively large cities are located only in the initial section—Shirvan (87,000 residents), Imishli (35,800), and later, Nakhchivan (94,500).

For Armenia, this segment is also relatively short (43.5 km) and sparsely populated. The largest settlement along the corridor is the town of Meghri, with a population of just 4,500.

In contrast, the alternative route passing through northern Armenia—Kars–Gyumri–Vanadzor–Gazakh–Baku—traverses the second and third largest cities of Armenia: Gyumri (112,300 residents) and Vanadzor (75,100), as well as Dilijan (15,900; also a major tourist destination) and Ijevan (18,700). The three northern provinces of Armenia—Shirak, Lori, and Tavush—constitute the country’s second most significant demographic cluster after the Ararat Valley and surrounding regions.

These areas have seen sharp population decline since the collapse of the Soviet Union (Vanadzor, formerly Kirovakan, decreased from 173,000 to 75,000; Gyumri, formerly Leninakan, from 230,000 to 112,000). Once the Vanadzor–Fioletovo railway segment is constructed, Vanadzor is set to become an important railway hub on the North–South axis (linking Iran–Nakhchivan–Armenia–Georgia–Black Sea).

On the Azerbaijani side, this route passes through the country’s most densely populated but underdeveloped central and western regions. Near the Armenian border, the railway crosses several district centers—Gazakh, Aghstafa, Tovuz, and Shamkir. It also includes Ganja, Azerbaijan’s third-largest city by population, a historic center of the western region and the capital of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic from May to September 1918. Due to economic isolation of the western part of Azerbaijan from its eastern regions, Ganja has lost its status as the country’s second city, which has now been assumed by Sumgait (430,000 residents).

The route also includes Yevlakh, an important railway junction from which the network branches south to Stepanakert and north to Balaken. Azerbaijan’s fourth-largest city, Mingachevir (106,000 residents), is also connected to the railway via a separate branch line.

Map 8․ Population Density Map of Azerbaijan by Administrative Units[11]

Due to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and weak connections with Baku, the densely populated western regions of Azerbaijan have lost much of their former role since the country’s independence and remain economically underdeveloped.

From a demographic standpoint, a similar pattern is observed in eastern Turkey. The railway route passing through northern Armenia offers the shortest land connection between Turkey and Central Asia and serves as an opportunity to stimulate development in Turkey’s underdeveloped eastern provinces. With the opening of the Ankara–Sivas high-speed railway line in 2023, the possibility has emerged to extend this line to Kars, turning the city into a major railway hub. In the case of the Kars–Gyumri–Vanadzor–Gazakh–Baku route, Kars plays an irreplaceable role and becomes a key node for eastern Turkey. In contrast, the freight routes from Azerbaijan to Georgian ports bypass eastern Turkey’s landlocked region and compete with Turkish infrastructure development plans.

Economic Interdependence as a Path to Long-Term Conflict Resolution

The so-called “Zangezur Corridor,” as proposed by Azerbaijan, envisions Armenia’s exclusion from vital regional transport routes and perpetuates the zero-sum logic and competitive relations developed during the conflict. In contrast, the Kars–Gyumri–Vanadzor–Gazakh–Baku railway creates economic interdependence between three historically adversarial countries—Turkey, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. This route has the potential to revitalize border regions in all three countries that have suffered from decades of blockade, border tensions, and severed economic ties.

Through mutually beneficial cooperation, it becomes possible to gradually shift societal perspectives and reframe the conflict-ridden past. The operation and maintenance of new infrastructure will also require political and economic coordination and the creation of joint mechanisms to enhance efficiency.

Conclusion

The railway networks in the South Caucasus were initially developed during the Russian Empire and Soviet era, primarily for military-political purposes: to connect the region to the imperial center and support strategic expansion. In the post-Soviet era, infrastructure planning has often sought to bypass Armenian territory, ignoring the need for optimal East–West connectivity. Within the context of the “Middle Corridor,” the creation of new communication routes should reflect a new logic—one that prioritizes optimal connections. Among these, the railway passing through northern Armenia offers competitive advantages over both the northern (via Georgia) and the Azerbaijani-proposed “Zangezur Corridor” routes.

Samvel Meliksetyan

[1] https://zametki-geo.livejournal.com

[2]https://zametki-geo.livejournal.com/9689.html

[3] https://ic.pics.livejournal.com/clio_historia/86301992/16366059/16366059_original.jpg

[4]https://stem-lab.az/en/article/cargo-traffic-on-the-middle-corridor-increased-by-62-in-2024-1284#:~:text=Cargo%20traffic%20along%20the%20Trans,2024%2C%20reaching%204.5%20million%20tons

[5] https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/6248f697aed4be0f770d319dcaa4ca52-0080062023/original/Middle-Trade-and-Transport-Corridor-World-Bank-FINAL.pdf

[6] https://bm.ge/ru/news/zangezurskii-koridor-uvelicit-propusknuiu-sposobnost-srednego-koridora-do-10-mln-tonn

[7] https://caliber.az/post/azpromo-alyatskij-port-planiruet-uvelichit-propusknuyu-sposobnost

[8] https://russian.news.cn/20231221/ae9c229aa282401bbd2118de76f998d6/c.html

[9] https://www.railway.supply/nachalos-stroitelstvo-zheleznoj-dorogi-kitaj-kyrgyzstan-uzbekistan/

[10] https://earth.google.com/earth/d/19_sjuVo-u-jyt2N4O-f8XiHyx9_zuu7r?usp=sharing

[11]https://www.geo-ref.net/pdf/azerbaijan.pdf