Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, all newly independent republics faced the challenge of delimiting and demarcating their former inter-republican borders. In the western part of the USSR, including the South Caucasus, the Soviet Union’s external borders were already delimited. In Armenia’s case, these were the borders with Turkey and Iran.

Among the former Soviet republics, Armenia’s border with Azerbaijan had already transformed into a zone of hostilities of varying intensity during the Soviet era, particularly from January 1990 onwards. Since 1994, it has been fortified with defensive structures and heavily mined, effectively serving as a line of contact.

Georgia was the only state with which Armenia established a joint border delimitation commission in 1995. During the commission’s first fifteen years of work, which concluded in the early 2010s, agreement was reached on approximately 147 km[i] of the Armenian-Georgian border’s total length of about 225 km, though some sources cite 160 km[ii]։ This situation has remained largely unchanged to this day. (The discrepancy in figures regarding the length of the border and the delimited sections stems from methodological differences in the calculations used by both sides.)

Formation and Specificities of the Border

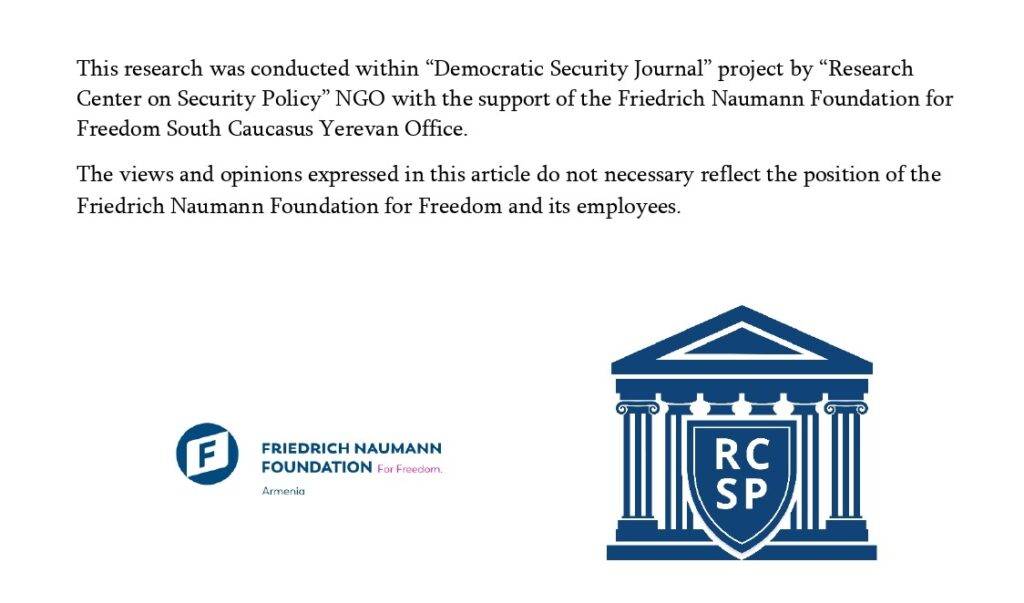

The present Armenian-Georgian border was established in the 1920s and 1930s and has remained largely unchanged since. It was based either on earlier administrative boundaries from the Tsarist era (covering the entire Shirak section and a small northeastern corner of Tavush province) or on the ceasefire line from the 1918 Armenian-Georgian war, which also served as the northern boundary of the “neutral zone” of Lori in 1919-1920.

Map 1: The Neutral Zone of Lori (in light yellow), 1919-1920[iii]

On November 6, 1921, the Soviet authorities of Armenia and Georgia signed a border agreement that, with minor modifications, remained in force thereafter. As mentioned earlier, the Armenian-Georgian border, like the Armenian-Azerbaijani border in Tavush and Syunik, was shaped by the military conflicts of 1918-1921 and largely corresponds to the delimitation lines of that period.

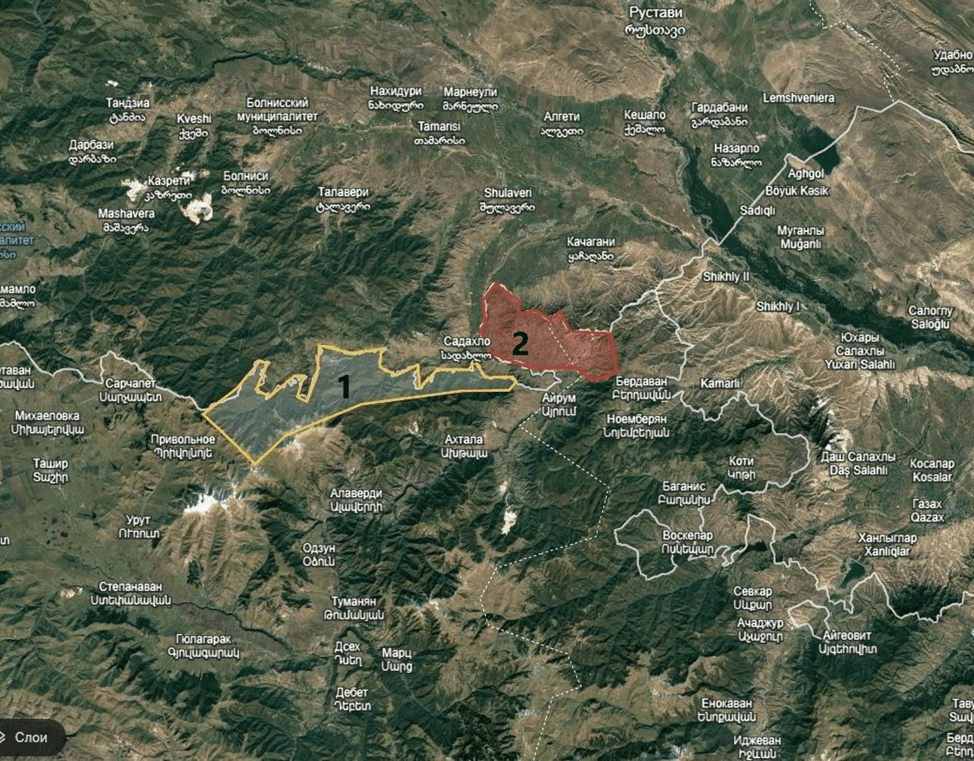

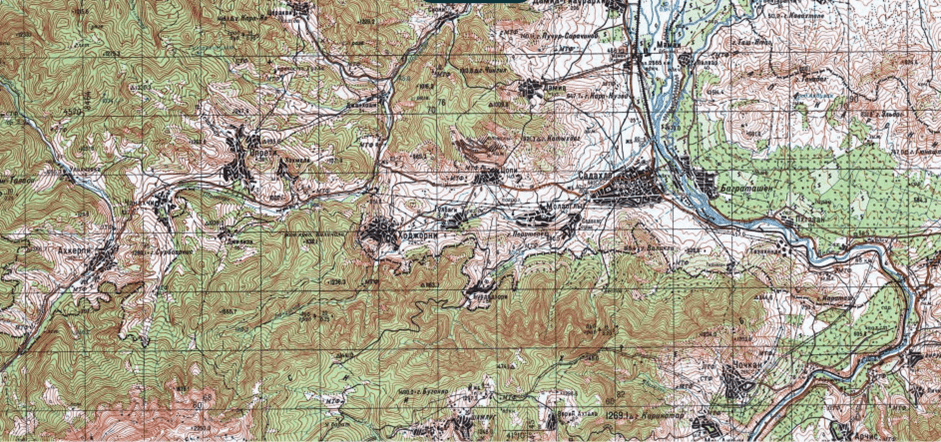

A key difference between the Armenian-Azerbaijani border and the Armenian-Georgian border is that in the former case, the fate of border-adjacent settlements was determined based on ethnographic principles, aiming to prevent Armenian villages from being included in Azerbaijan and vice versa. This led to the formation of enclaves. In contrast, no such antagonism existed along the Armenian-Georgian border. Although several Armenian-populated villages (Aghkyorpi, Chanakhchi, Burdadzor, Khokhmeli, Gyulbagh, and Khojorni) were located along the border with Georgia in the Lori neutral zone, they were transferred to the Georgian SSR, while two Azerbaijani-populated villages in the disputed area—Lambalu (now Bagratashen) and Kyurplu (now Zorakan)—were incorporated into the Armenian SSR.

Map 2: Key Disputed Sections of the Armenian-Georgian Border in the 1920s

During the first decade of Soviet rule, the primary disputes concerning the Armenian-Georgian border were concentrated in its eastern section. These involved the ownership of the Lalvar forest, which extended northward from the Virahayotz (Somkheti) mountain range to the present border, as well as the status of Armenian-populated border villages remaining within Georgia and the administrative affiliation of the Azerbaijani-populated villages of Lambalu and Kyurplu.

The issue of the forest and villages north of the Lalvar mountain massif was raised multiple times, with several decisions being made regarding their status. In 1929, some Armenian-populated border villages (Aghkyorpi, Chanakhchi, Burdadzor) were transferred to the Armenian SSR[iv], but were returned to Georgia in 1933. As a result, the Armenian-Georgian border took on the form it retained until the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Map 3: Detailed 1932 Map of the Armenian SSR, Showing Armenian-Populated Villages within Soviet Armenia[v]

Under Soviet rule, Armenian villages located immediately along the border within Georgia had access to Armenia’s forests, pastures, and water resources, as well as close ties with Armenian villages south of the border. Some of these, such as Aghkyorpi, Khojorni, and Burdadzor, were almost entirely surrounded by Armenian SSR territory. The border region of the Tashir and Noyemberyan areas also had significant interactions between Azerbaijani-populated villages on both sides of the border.

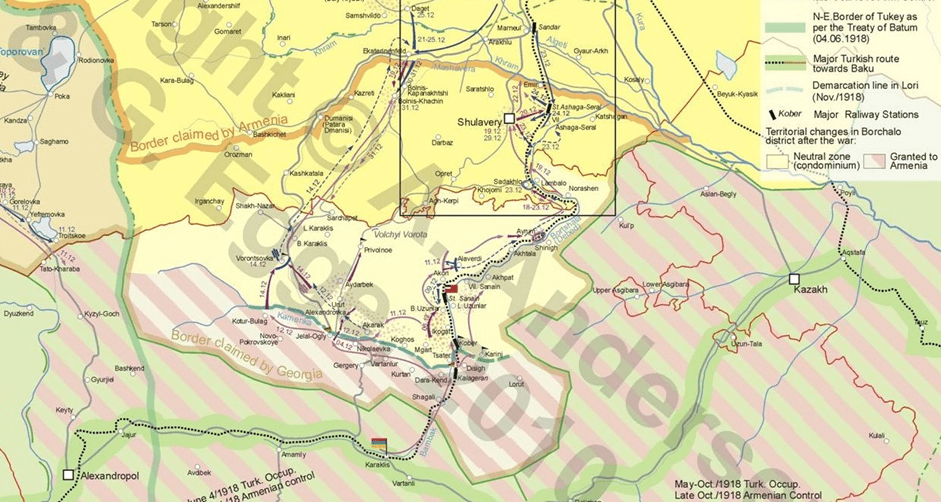

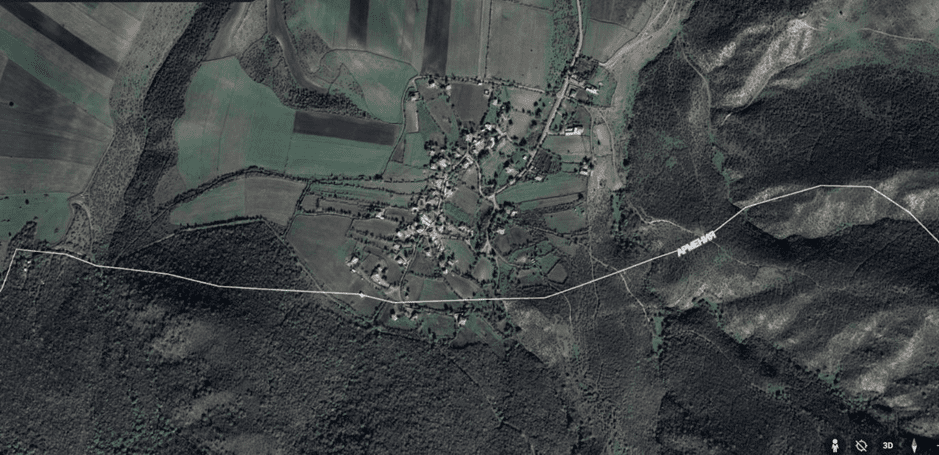

After 1988, such interactions ceased, and following Armenia’s independence, numerous challenges arose for the Armenian-populated villages along the border. These issues became even more pronounced in the 2000s due to increased border restrictions. North of the Armenian border, several Azerbaijani-populated villages that had previously utilized Armenian territory also exist. One particularly contentious case involves the Azerbaijani-populated village of Burma in Georgia’s Marneuli region, where several houses are located either adjacent to or within Armenia’s administrative territory, making it one of the ongoing border disputes.

In 2011, residents of Burma, along with those from the nearby Azerbaijani-populated villages of Sadakhlo and Tazakend, protested Armenian border guards’ seizure of approximately 20 hectares of land that they had been using.[vi]

Map 4: The Azerbaijani-Populated Village of Burma Along the Armenian-Georgian Border, with Some Houses Located within Armenia

The bilateral border delimitation commission, established in 1995, was particularly active in 2003 and 2009-2011. In 2009, negotiations on the Armenian-Georgian border resumed, with statements affirming the continuation of the process. In recent years, discussions have focused on the potential transfer of a disputed land plot in the Bavra area of Armenia’s Shirak province to Georgia, in exchange for the return of the Armenian-populated village of Khojorni[vii]՝ in Georgia’s Marneuli region to Armenia.

Although both sides have consistently emphasized a constructive atmosphere in negotiations, no significant progress has been made beyond the already agreed-upon sections of the border. Within the broader context of Armenian-Georgian border issues, media in both countries have periodically raised concerns regarding Javakheti and Northern Lori from the Armenian side, and the historical ownership of Lori province from the Georgian side. However, these topics have no bearing on the delimitation process itself.

Discussions regarding the Armenian-Georgian border delimitation briefly resurfaced in 2021 in parallel with negotiations on the same process with Azerbaijan. The necessity of border delimitation was reiterated in January 2024 within the framework of the “Declaration on the Establishment of a Strategic Partnership between the Republic of Armenia and Georgia.” The topic was also raised in April and during the summer of 2024, amid the ongoing delimitation of the Armenian-Azerbaijani border in the “four villages” area.

One of the key factors slowing down the process is the pre-election and post-election political developments in Georgia.

Following the joint Armenian-Azerbaijani border delimitation commission’s statement[viii] on January 16, 2025, the continuation of this process from the point where the borders of the three states intersect implies Georgia’s involvement and the signing of a trilateral agreement to define the tripoint.

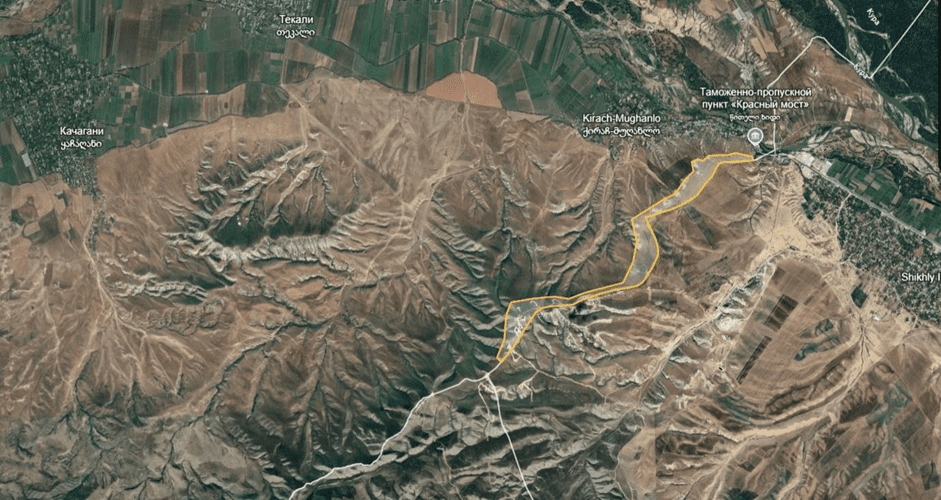

The significance of issues concerning the tripoint is further underscored by the fact that, around 2008, Azerbaijani forces took positions on the summit and northern slopes of the Papakar Heights, which are located in Georgia’s territory adjacent to Armenia, effectively occupying around 1,000-1,200 hectares[ix] of Georgian land. In the same area, the Armenian armed forces also maintain a few outposts within Georgia’s administrative territory, albeit with a significantly smaller encroachment.

By signing a trilateral agreement, the parties would be able to continue the process bilaterally, potentially fostering a constructive competitive dynamic in parallel negotiations.

Map 5: Azerbaijani Military Positions in Georgian Territory East of the Tripoint

Key Issues in the Delimitation of the Armenian-Georgian Border

The Armenian-Georgian border can be divided into two main sections. The first, the western segment, runs through a high-altitude open area where settlements are located at a considerable distance from the border, and, for the most part, there are no disputed sections (with the exception of the area adjacent to the village of Bavra and its border checkpoint).

The second section, east of the village of Metsavan, though largely following the watershed line of the mountain range, presents greater complexity due to forested areas, intricate border geometry, and settlements located in close proximity to the borderline. In the Akhkyorpi-Debed section, on the Georgian side, the settlements adjacent to the border include predominantly Armenian-populated villages such as Akhkyorpi, Chanakhchi, Opreti, Khokhmeli, Khojorni, Gyulbagh, and Burdadzor, as well as Azerbaijani-populated villages like Mollaoghli, Burma, Sadakhlo, and Tazakend. Further east, the border follows the Debed River and the Papakar mountain range. On the Armenian side, the village of Jiliza is located in this segment.

Map 6: The Most Complex Section of the Armenian-Georgian Border – Akhkyorpi-Sadakhlo Segment[x]

The residents of these villages have historically relied on Armenia’s forest, water resources, and pastures. Their close proximity to the border raises numerous issues that need to be addressed during the delimitation process. The principles outlined in the OSCE guidelines[xi], which also form the basis of the Armenian-Azerbaijani border delimitation regulations, can help provide optimal solutions. Additionally, the expertise of EU member states, particularly Lithuanian specialists who contributed to drafting the OSCE guidelines, could be useful. The EU’s mediation may also be beneficial in a technical capacity, for instance, by providing up-to-date satellite imagery and other technical support necessary for border mapping.

I have previously analyzed the practical application of these approaches using examples from the Armenian-Azerbaijani border[xii]. Similar methodologies in the Armenian-Georgian border delimitation process could also positively impact Armenian-Azerbaijani negotiations, where similar issues exist but are compounded by a higher degree of political tension and conflict intensity.

For the Akhkyorpi-Burdadzor segment, the presence of a new checkpoint in the direction of the Armenian village of Jiliza is also crucial, given the traditional connectivity between these villages and the northern part of the Alaverdi region, as well as the fact that some residents have settled in Armenia.

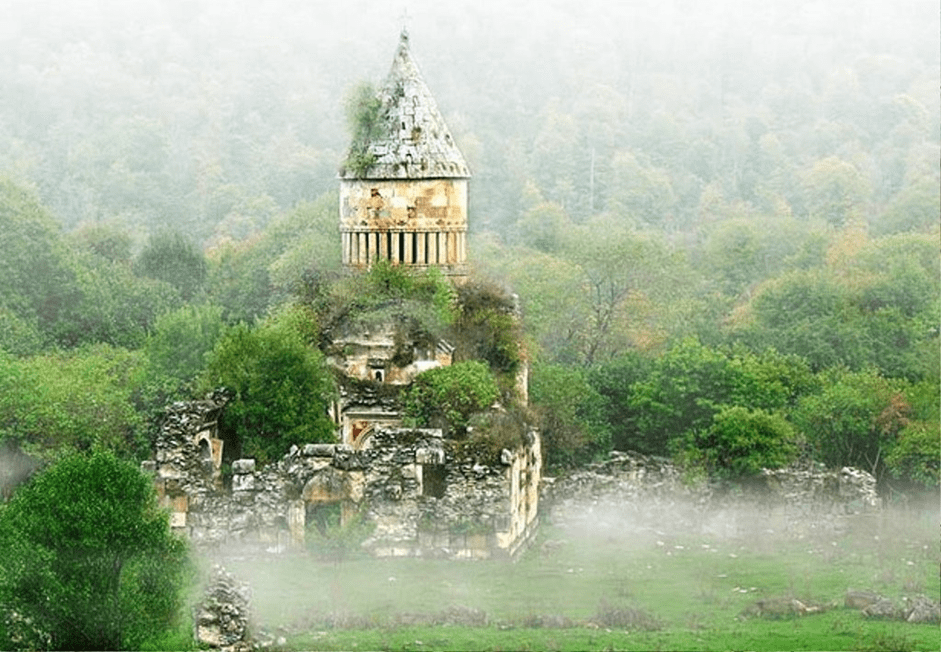

An important issue in Armenian-Georgian relations is the fate of historical monuments located in the border zone, particularly medieval Armenian (Khorakert Monastery, Khojorni Church) and Georgian (Khujapi Monastery) religious complexes. The border status complicates both the preservation of these monuments and access to them. A potential solution could involve an exchange of monuments (as Khujapi is located in Armenia, while Khorakert and Khojorni Church are in Georgia) or the establishment of special agreements and regulations allowing unrestricted access for religious and tourism purposes. The border status also hinders the restoration efforts for these monuments, necessitating joint solutions.

Picture 1: The 13th-century Khorkhert Monastery on the Georgian side of the Armenia-Georgia border

This factor could have a positive impact on the fate of historical sites in the Armenian-Azerbaijani border zone, such as Gaga Fortress, St. Sargis Church, and Tsitsernavank. Moreover, it could contribute to resolving one of the most contentious issues in Georgian-Azerbaijani border delimitation—concerning the David Gareji Monastic Complex and several other religious sites located in Azerbaijan.

Conclusion

In the presence of political will, the Armenian-Georgian border does not present serious challenges, as most of the issues are technical in nature. The completion of the border delimitation process could positively influence both bilateral relations between the two countries and the border delimitation processes between Armenia and Azerbaijan as well as Georgia and Azerbaijan.

For issues that cannot be resolved through compromise, international expert arbitration or formal adjudication, with support from the EU, could serve as alternative solutions. The International Court of Justice, as the highest global legal authority, is also competent to examine such matters.

The Armenian-Georgian border is the only Armenian border fully controlled by Armenian border guards. The U.S. has already supported the implementation of new border management mechanisms in this sector. Notably, the signing of the Armenia-U.S. Strategic Partnership Charter in Washington on January 14 underscores the importance of ensuring that border delimitation, management, and cross-border cooperation efforts on this front serve as exemplary models for the management of Armenia’s other borders.

[i] https://hy.armradio.am/archives/357500

[ii] Shamkharadze N. Georgian State Border – Past and Present, http://css.ge/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/nika_border_eng.pdf

[iii] http://www.conflicts.rem33.com/images/Georgia/arm_geor_war/map%204.jpg

[iv] K. Khachatryan, H. Sukiassyan, The Process of Resolving Armenian-Georgian Territorial and Border Issues in the 1920s-1930s, Questions of Oriental Studies, No. 11, Yerevan, 2015, pp. 75-97

[v] https://www.loc.gov/item/2014585716/

[vi] http://janarmenian.ru/news/3895.html

[vii] https://www.panorama.am/ru/news/2009/09/16/azg/1209881

[viii] https://www.mfa.am/hy/press-releases/2025/01/16/arm_az/13039

[ix] https://www.panarmenian.net/m/rus/news/229791

[x] 1976 USSR General Staff Map: https://maps.vlasenko.net/smtm100/k-38-102.jpg

[xi] https://www.osce.org/ru/secretariat/363471

[xii] https://rcsp.am/entry/4679/sahmanazatman-kanonakarg-qaxaqakan-ev-bovandakayin-yurahatkutynnery/

Photo: Public Radio website

Author: RCSP associate expert Samvel Meliksetyan