Geopolitical Context of Armenian-Russian Relations and Russia’s Aspirations in the Region Since the 1990s

Russia’s foreign policy, as the successor to the Soviet Union that lost the Cold War, has maintained several inertial manifestations of the former state’s foreign policy since the early 1990s, although these became more pronounced from the 2000s. The main elements of Russian foreign policy were maintaining influence in the post-Soviet region, competitive relations with the West and its associated military-political structures (NATO), and neutralizing concerning movements and ideological trends in Russia’s internal political developments (initially separatist movements and political Islam, later “color revolutions” and political opposition).

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the West recognized the legitimate interests of the Russian side as a supreme arbiter in the post-Soviet region, which could resolve dangerous interstate and ethnic conflicts (Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Transnistria, Tajikistan). For the same reason, the West supported Russia in becoming the sole owner of the former USSR’s nuclear weapons, viewing it as a more predictable and legitimate party than other post-Soviet countries that had such arsenals on their territory (Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan).

The first obvious geopolitical contradictions between Russia and the West became apparent in the mid-1990s in connection with inter-ethnic conflicts in the former Yugoslavia and the 1999 bombing of Yugoslavia. However, the new phase of conflict after the USSR’s collapse began an escalation dynamic in 2003-2004, when revolutions took place in Georgia and Ukraine under new political elites and ideas with Western orientation. In parallel, in 2004, three former Soviet republics—Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—became NATO members. The repetition of the same scenario in other post-Soviet states (internal changes with new pro-Western elites, and external orientation through membership in NATO, the EU, and other Western structures) led to the hardening of Russian positions and a more direct and decisive struggle for the post-Soviet region, which was expressed in V. Putin’s 2007 Munich speech[i]. This was followed by Russia’s military aggression against Georgia in 2008 with the de facto seizure of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, the annexation of Crimea, and the Donbas war in 2014. The Russian-Ukrainian war of 2022 is a development of the same logic.

After 2008, Russia also became more active in the South Caucasus, trying to become a direct mediator in the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict. This format implied interim solutions to the Nagorno-Karabakh issue, which meant abandoning unilateral support for Armenia. Azerbaijan—the region’s largest and energy-rich country—had chosen formats since the late 1990s that bypassed and competed with Russia’s integration programs in the post-Soviet space (GUAM – Georgia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, Moldova) and was considered an important country in creating gas and oil infrastructure bypassing Russia (Nabucco). Therefore, political trade with Azerbaijan was a primary issue for Russia in the South Caucasus. This factor explains, in particular, the large-scale sale of weapons to Azerbaijan that began in 2007-2008, the volume of which reached approximately $5 billion by the end of the 2010s[ii].

Therefore, the conflict with the West led to an increase in Russia’s determination to strengthen the foundations of its influence in the post-Soviet region. Various tools were used for this purpose: political pressure, military intervention, mediation aimed at resolving conflicts, energy and economic blackmail and dividends. This particularly applies to countries located west of Russia (Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova) and in the South Caucasus, which have the possibility of an alternative to strengthen relations with the West. The alternative options for Central Asian countries toward the west were limited by geographical factors and the South Caucasus, while communications with China were still in the development phase.

Russia’s and Armenia’s New Aspirations in the South Caucasus and Possible Relationship Scenarios

During the Ukrainian war, Russia’s aspirations in the South Caucasus are aimed at maintaining influence or halting the pace of weakening, with expectations of strengthening in the future. Here, it can be noted as a general logic that if Russia’s capabilities (political, military, permission or inaction of other international actors that could obstruct) are sufficient, the country will strive to have hegemony over the entire region, and if they are not sufficient, over only one country, which will serve as a tool against other parties.

The most interesting country from this perspective is Azerbaijan, which has a key role in the context of all communication projects going from Türkiye and Europe to Central Asia. Azerbaijan, however, also has external patronage in the form of Türkiye, and possible Russian pressures on that country are limited. Therefore, for the loyalty of the Azerbaijani side, the Russian side is ready to make concessions and interesting offers to that side (as blackmail tools are more limited and risky). This is a trend that was evident in Armenian-Russian relations since the early 2010s—to involve Azerbaijan in the Russian sphere of influence or make it a loyal country through concessions from the Armenian side, and this logic remains relevant in the case of Russian hegemony in the region. The main long-term goal of the Russian side is to maintain control over regional infrastructure and not allow the Armenian-Azerbaijani settlement to lead to the weakening of its positions and create an occasion to leave the territory of the South Caucasus (the 102nd military base in Gyumri and Russian border guards on the Armenia-Iran and Armenia-Türkiye borders).

Based on the above, the tactics of the Armenian and Azerbaijani sides with Russia depend on the involvement of other external parties (primarily the US), through which possible Russian intervention can be neutralized. The greater the involvement of the West, the greater the determination of the parties to counter the Russian factor and move toward mutual settlement of relations.

When addressing future scenarios of Russian policy in the South Caucasus, several factors are important, which serve as axioms for constructing these scenarios.

First, the results of the Ukrainian war and Russia’s resources in the aftermath. If the Russian side maintains sufficient resources, then its main tactic in the South Caucasus will be a policy of maximizing its own interests and keeping the entire region, with all parties, under its influence.

If for various reasons Russia’s possibilities for intervention in the region become limited, then maintaining influence over at least one side can be considered as the main tactic, which will allow it to influence other parties as well. Armenia and Georgia are more vulnerable here.

The main regional issue that makes everyone vulnerable is the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict, which allows the Russian side to maintain leverage over the entire region.

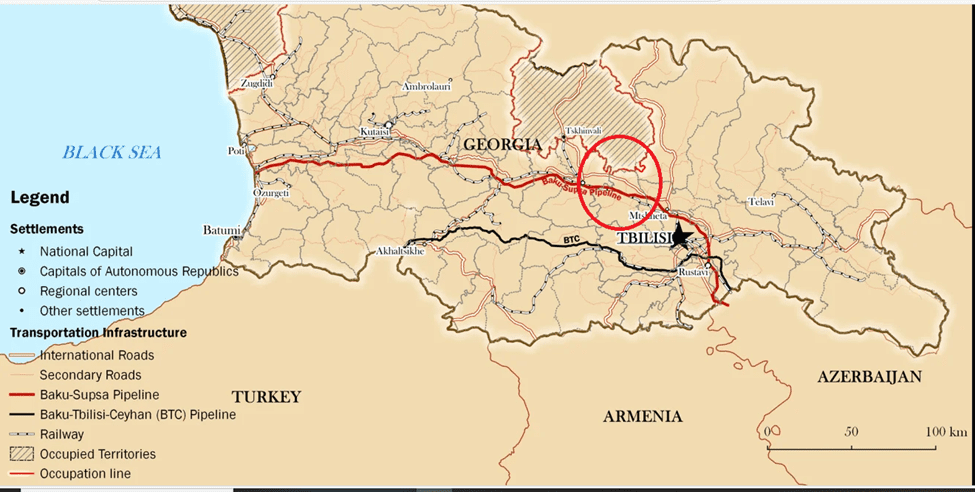

If the conflict persists and Russia loses its influence over Georgia and Azerbaijan (which are becoming a route for the East-West transport corridor), but maintains it over Armenia, it can cut all communications along the East-West line passing through Georgia, which are located 350 meters (highway leading to the Black Sea) and 8.4 km (railway leading to the Black Sea) from the Russian influence border in South Ossetia (or Tskhinvali region).

The main communications leading from eastern to western Georgia in the immediate vicinity of Russian-controlled South Ossetia (the red frame inside)

In the case of normalization of Armenian-Azerbaijani relations, the East-West communications through the central and northern parts of Armenia and Azerbaijan are far from the Russian border, and Turkiye’s involvement in this corridor provides an additional guarantee of their security.

The next thesis is that under conditions of low Western involvement, the mutual rapprochement of regional countries and the creation of cooperation are important for countering possible Russian influence and intervention.

The last thesis asserts that maintaining Russian influence implies the preservation of certain conflicts between or within countries and unresolved elements in relationships.

Bad scenarios for regional countries imply weakening Western positions and strengthening Russian positions, while good scenarios imply strengthening Western positions, regional cooperation, and activation of communications.

Model One (“post-Soviet hegemony”/”Russian Transcaucasia”): At the end of the Ukrainian war, the Russian side agrees with the US on recognizing the post-Soviet region as its sphere of influence. In this case, with the preservation of the current conflictual nature of relations, Armenia and Azerbaijan will not have the corresponding resources to resist Russian pressures and will accept the format stemming from “November 9,” especially regarding communications. By strengthening its positions in Armenia and Azerbaijan, Russia gains the opportunity to strengthen its influence over Georgia as well, and the South Caucasus will remain entirely under Russian control.

According to this model, the Russian side also maintains its influence over Central Asia and cancels the East-West communication routes to guarantee its trade and economic activities along the North-South line.

Model Two: The South Caucasus is not recognized as a Russian sphere of influence but is accepted as a buffer region whose countries must remain neutral. In this case, although Russia does not gain full control over the parties and communications, it maintains its current influence and gains the opportunity to buy time with the expectation of strengthening its positions in the future.

Model Three (Russia-West Confrontation in the South Caucasus Region)։ The results of the Ukrainian war do not establish any agreement regarding the South Caucasus, and competition between the West and Russia continues in the region. The Russian side is trying to strengthen its position by using various leverages on the parties: trade-economic and energy dependence in the case of Armenia and Georgia, and national minorities in the case of Azerbaijan. One of the possible leverages on Armenia is also influence on the internal political field and election results, which is relevant in all scenarios.

In this case, scenario development depends on the resolution of the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict and the extent of Western and Turkish involvement. If Armenia and Azerbaijan cannot find political will and additional guarantees to normalize relations, and Western involvement is weak, the Russian side’s competitive position will be more successful. Conversely, if the opposite occurs, scenarios aimed at conflict resolution and opening regional communications will strengthen.

Model Four (Collapse or Repetition of 1917)։ The freezing or end of the war in Ukraine leads to an internal political crisis in Russia, resulting in the Russian side abandoning the South Caucasus. For the region, this is dangerous from the perspective of possible military clashes in the North Caucasus and problems with trade-economic and energy communications with Russia. For Georgia and Azerbaijan, the dangerous impact is also the possible transfer of military operations to their territory, where representatives of North Caucasian ethnic groups live. For the Georgian side, this is also an opportunity to resolve its separatist territories issue by military means, which also carries risks of involving various groups from the North Caucasus. Related to this scenario, one can expect the withdrawal of the Russian military base from the territory of Armenia. The South Caucasus countries can solve the emerging problems only through joint efforts and minimization of risks in mutual relations.

Among the mentioned models, I consider the third model the most likely, although the impact of these factors may differ significantly.

Conclusion: Russia’s policy towards the South Caucasus and Armenia in short-term and medium-term scenarios depends on several factors:

a) The results of the Ukrainian war and its impact on Russia’s capabilities

b) Competition between the West (US, EU, individual states) and regional powers (Turkey, Iran) with Russia for influence in the region and the implementation of East-West communications

c) The nature and direction of relations between the three South Caucasus countries (conflict/zero-sum game or cooperation)

In all scenarios, I consider the third point particularly important—the rapprochement of Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan and the creation of regional formats that will allow these countries to minimize possible risks in all scenarios of external factor changes. In this context, the normalization of Armenian-Azerbaijani relations can also increase Georgia’s resilience.

As a theoretical proposal, the creation of a South Caucasus-Central Asia countries cooperation format can also be considered.

Samvel Meliksetyan

[i] https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/02/18/putin-speech-wake-up-call-post-cold-war-order-liberal-2007-00009918

[ii] https://ria.ru/20180901/1527658900.html