One of the most problematic elements in the regulation of Armenia-Azerbaijan relations in practice remains the issue of the status of the road passing through southern Armenia, which could create a direct connection between the main territory of Azerbaijan and the Nakhijevan Autonomous Republic (NAR). The article presents the history of Nakhijevan’s transport connections and proposes several solutions for the Azerbaijani and Armenian sides.

History of Nakhijevan’s Transport Connections

The present-day Nakhijevan Autonomous Republic was formed from the plain and mountainous sections of the middle Arax River valley basin, where infrastructure mainly extends through river valleys, and the main transport route stretched from the north along the Arax River to Jugha (Julfa), from where it crossed into present-day northern Iran via a bridge since ancient times. Since antiquity, the main and most important trade route connecting Armenia’s capital central region (Ararat Plain) with Iran and Asia Minor also passed through the Arax valley. This route also served as the main path for invasions into Armenia from the southwest.

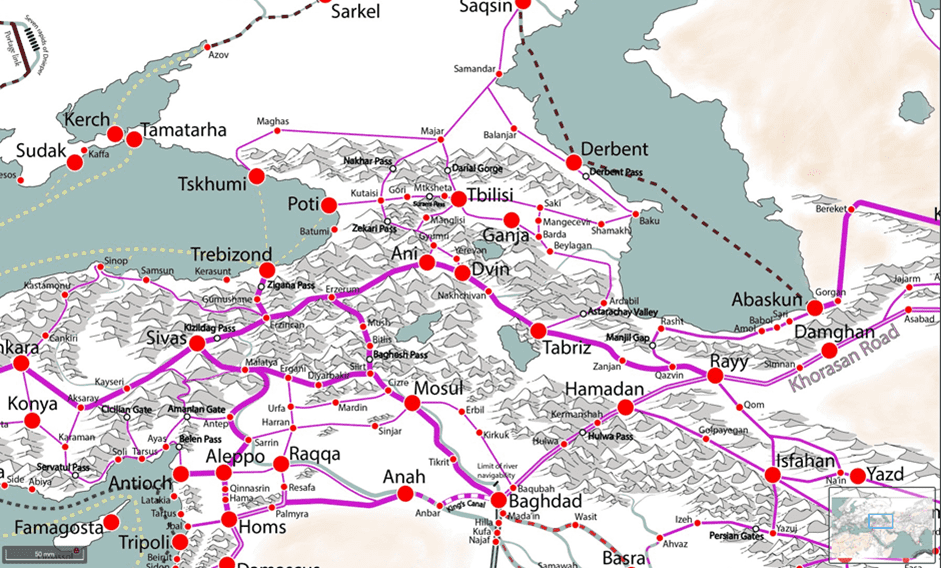

Regional section of Martin Manson’s map of medieval trade routes. One of the main trade routes from Iran to China—Central Asia—Armenia—Byzantium passes through the Arax valley and Nakhijevan[1]

At the same time, the Meghri gorge, whose complex mountainous relief hindered road infrastructure along the Arax shore, has been a historical dividing line between the middle Arax valley and the Kura river valleys, and in the past no road along the Arax shore crossed Meghri toward the Caspian Sea. The Nakhijevan region had transport connections with Yerevan, with Vayots Dzor through several river valleys (Vayots Dzor was part of the Nakhijevan khanate at the time of the region’s conquest by Russia), and also with the Sisian region, which was often part of the Nakhijevan historical region or khanate and was conquered by the latter only during the time of Karabagh Khan Ibrahim (late 18th century). There was also no road or connection passing through Meghri during that period. This picture was preserved later as well.

The Russian Empire, moving southeast from Tiflis (Tbilisi) through the Kura valley from 1804 and conquering all the Muslim khanates of the Kura basin by 1806, could not conquer not only Yerevan and Nakhijevan, which belonged to the Arax river basin, but also, due to the absence of infrastructure, was forced to leave under Persian rule until 1826 the entire mountainous, difficult-to-access section south of Kapan—up to Meghri—which belonged to the Karabagh khanate and had come under its jurisdiction. These territories passed to the Russian Empire only in 1828 as a result of the Treaty of Turkmenchay and initially formed part of the Armenian Province.

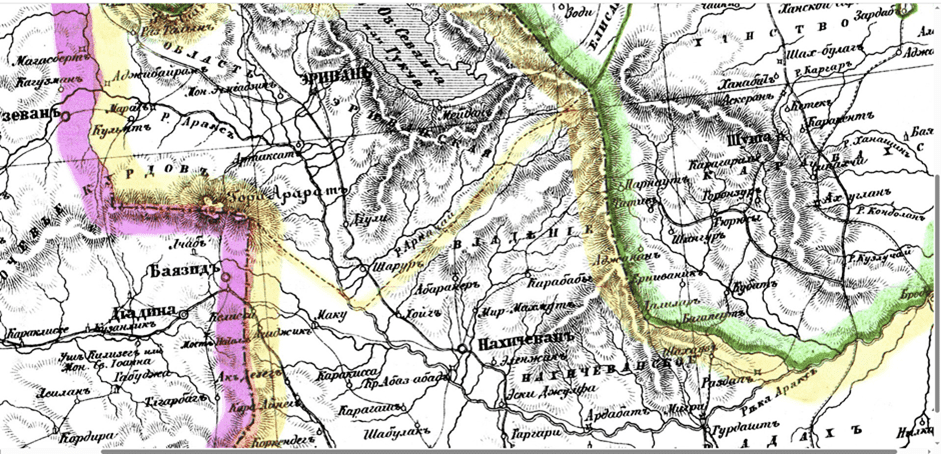

Borders of Persia and the Russian Empire before 1828[2]

During the imperial period, the new administrative policy and infrastructure construction also preserved the old geographical logic. Nakhijevan was located within the Armenian Province (later the Yerevan Governorate), Zangezur-Syunik within Elizavetpol. The only suitable road from the territory of present-day Azerbaijan that connected it with the Nakhijevan region was the Yevlakh-Shushi-Goris-Sisian-Bichaanak-Nakhijevan route, whose quality was particularly poor in the Goris-Nakhijevan section. It should be noted that the connections between the two regions were extremely weak.

The new railway connected Nakhijevan and Julfa with Yerevan in 1908 and continued to Northern Iran (Tabriz). In the last years of the Russian Empire, there were plans to build the Yevlakh-Shushi-Goris railway line, but there was no program to connect the Elizavetpol Governorate or Baku with Nakhijevan along the Arax shore. Nakhijevan’s infrastructure was considered in the context of the Tbilisi-Yerevan-Persia infrastructure line. A 1903 published road map of the Caucasus region showed a gravel-paved road (аробная дорога) from Nakhijevan to Ordubad, a road suitable for ox-drawn carts from Ordubad to Meghri, and only a path suitable for pack animals eastward from Meghri along the Arax shore. Although there was still no road in that section during the first period of Armenia’s independence in 1918, according to some sources, the Turkish side proposed exchanging Meghri for sections of Zangezur and Jevanshir (Kelbajar-Martakert).[3]

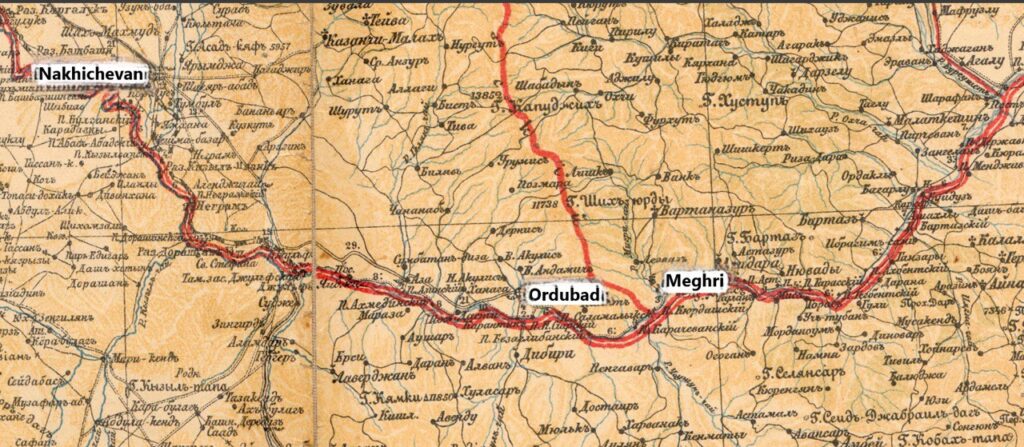

Roads in the Ordubad—Meghri section according to the 1903 map of Russian roads: Wheeled road up to Ordubad, road for carts from Ordubad to Meghri, suitable path for pack animals east of Meghri[4]

In June-July 1920, the Red Army entered Nakhijevan not along the Arax shore, but via the Goris-Bichaanak-Nakhijevan route. Although part of the Yerevan-Julfa railway remained within Nakhijevan occupied by the Bolsheviks, the August 10, 1920 agreement stipulated that the entire railway up to Julfa should remain under Armenian administration, as it connected Armenia with Persia.

After the establishment of Nakhijevan’s borders and the confirmation of autonomy (1921), the communications picture did not change significantly until the late 1930s. Such a large exclave was an anomaly for the Soviet Union until 1946 (the creation of the Kaliningrad Oblast within the RSFSR). The roads passing through Nakhijevan territory (Goris-Sisian-Bichaanak-Nakhijevan-Yerevan, Vayots Dzor – Sharur – Arax – Yerevan, Meghri-Nakhijevan-Yerevan) remained the main routes for connecting Syunik and Vayots Dzor with the main part of the Armenian SSR, while Nakhijevan’s connection with Azerbaijan was carried out via the same Shushi-Goris-Bichaanak-Nakhijevan route and the Nakhijevan-Yerevan-Tbilisi-Baku railway line.

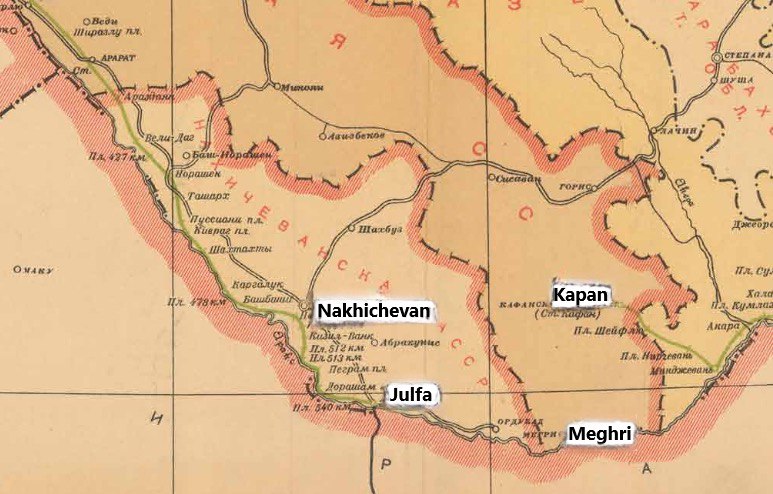

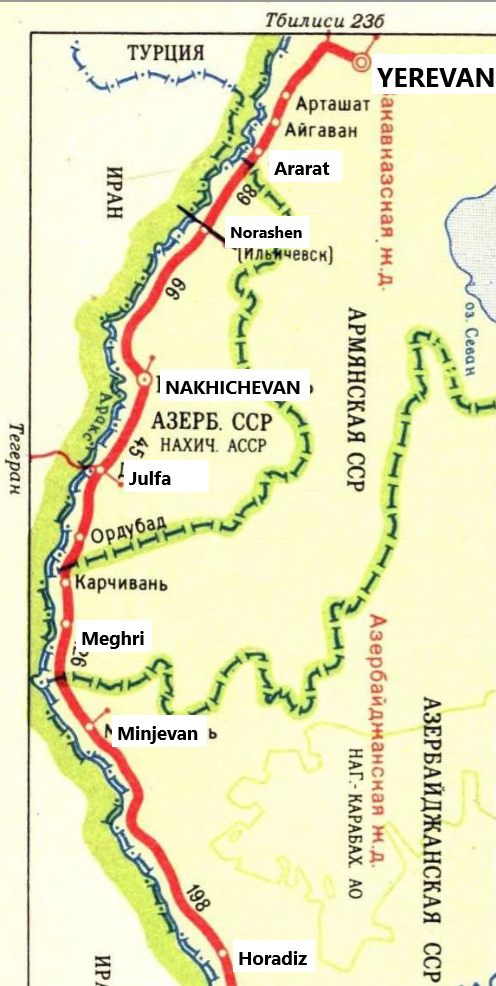

Automobile and railway (in green) roads in the Nakhijevan section, 1937[5]

The railway connecting Nakhijevan to Baku along the Arax shore and through the Meghri region was built only in 1941, whose main function was primarily for the military-political purpose of connecting Baku with northern Iran via the Julfa railway junction. From the 1950s, information has been preserved that the authorities of Soviet Azerbaijan proposed to Soviet Armenia to exchange the Meghri region for certain sections of Nakhijevan (Norashen-Sharur, salt mines). Interestingly, at least until the 1980s, the railway in the northern part of Nakhijevan—north of Bash-Norashen (now Sharur) station—was under the management of the Yerevan branch of the Transcaucasian Railways, while south of it, including the railway passing through Meghri, was under the Azerbaijani branch control.

Border of the Transcaucasian and Azerbaijani railways on the territory of the Nakhijevan ASSR, at Norashen station[6]

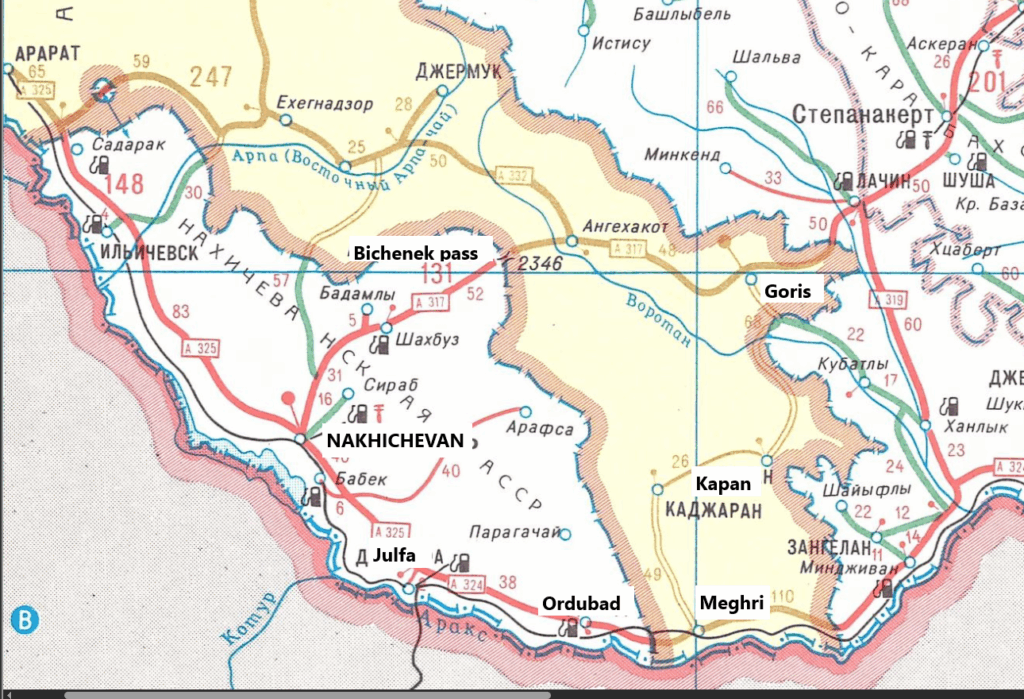

From the 1980s, the authorities of Soviet Azerbaijan tried to obtain agreement to build an automobile road through Meghri as well, which would connect the Nakhijevan ASSR with the main part of Azerbaijan, but the Armenian side opposed this proposal.[7] Until the beginning of the Karabagh conflict, Nakhijevan’s main connection with Baku was carried out by railway, while the main automobile road was the Nakhijevan-Bichaanak mountain pass-Goris-Stepanakert A-317 highway. It should be noted, however, that the functional condition of this road, especially in the Goris-Stepanakert section, was poor, and practically the main connection was carried out precisely by railway.

Map from the USSR 1986 road atlas

The Ordubad—Meghri—Zangelan A-324 republican highway is marked as operational (although there was no road east of Nyuvadi (now Nrnadzor) village)[8]

Due to the Karabagh conflict, the last train from Nakhijevan to Baku passed in April 1992. Starting in 1988, both Armenian trains passing through Yerevan to Meghri and Kapan, and Azerbaijani trains passing through Meghri were stoned or suffered other damage, which in contemporary Azerbaijani political discourse also serves as justification for special security guarantees for transport and persons passing through Meghri. In 1992, the border between Armenia and Nakhijevan was closed, and the exclave found itself in a semi-blockaded situation. Nakhijevan’s only connection with Azerbaijan was carried out through Iranian territory via the Julfa bridge. Under these conditions, the “Umud” (Hope) bridge was opened in May 1992, connecting Nakhijevan with Turkey, and reconstruction work began on Nakhijevan airport, built in 1976, as a result of which it gained the ability to receive heavier Tu-154 and Tu-137 aircrafts. As a result of modernization in 2004, Nakhijevan airport received international airport status and is capable of receiving aircraft weighing up to 400 tons.

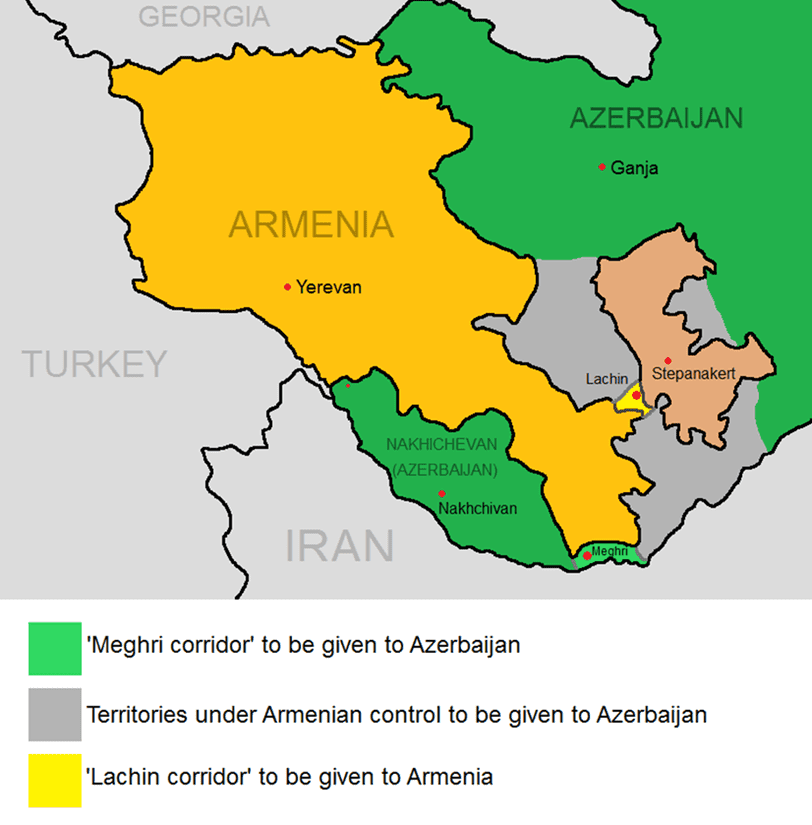

In 2007, a new bridge—Shahthakhti-Poldasht—was opened over the Arax River, which became the second operating automobile crossing point and bridge between Nakhijevan and Iran. Although during the frozen period of the Artsakh conflict, Nakhijevan definitively overcame its semi-blockaded state, the importance of the road passing through Meghri was also manifested in the context of various proposals aimed at resolving the conflict. One of these was the proposal by Turkish President Turgut Özal, whereby Nagorno-Karabagh would pass to Armenia, and the Meghri region to Azerbaijan. This proposal apparently formed the basis of Paul Goble’s first and second programs, which also envisioned such an exchange. Similar logic operated later as well—with the 1999 negotiations and the Key West process, with variants of territorial exchanges or an overhead sovereign road—an overpass—passing through Meghri.[9]

Variant of solutions to the Karabagh conflict through exchange logic

The issue of opening the railway passing through Meghri was discussed at least until 2005[10], although precisely during that period (2003)[11] a 32 km section (out of 43 km) of the railway passing through Meghri was dismantled.

Azerbaijan—Nakhijevan Connection After 2020 and Practical Proposals

The Armenian side’s defeat in the second Artsakh war caused the Azerbaijani side to secure the issue of unhindered connection with Nakhijevan through Point 9 of the November 9 statement. Previously, this issue had not been discussed in such a format, since the issue of privileged passage through Meghri was always connected to the question of Nagorno-Karabagh’s status and connection with Armenia. The presence of Point 9 of the November 9 statement was the basis for active exploitation in Russian and Azerbaijani political statements. The Azerbaijani side interpreted this point as agreement for a corridor, calling it the “Zangezur corridor”—unhindered passage through Armenian territory without customs procedures. Azerbaijan’s connection with Nakhijevan, according to the Azerbaijani approach, assumes restoration of the previously operating railway through Meghri and construction of an automobile road following the logic of the Lachin corridor. After establishing military control over the entire territory of Nagorno-Karabagh in 2023, the Azerbaijani side diversified its approaches to connecting with Nakhijevan, agreeing with Iran on the construction of railway and automobile roads along the southern shore of the Arax, which in Azerbaijani discourse received the name “Araz corridor.” The Azerbaijani and Iranian sides have already begun construction of a 418-meter-long bridge as well as border crossing infrastructure, which should be completed by the end of 2025 or early 2026.[12]

The length of the “Araz corridor” is 55 km, which is about 12 km longer than the road passing through Syunik territory. Thus, if it is implemented, the Azerbaijani side will have air connection with Nakhijevan, land connection through Iranian territory with two crossing points, whose length is comparable to the length of the road passing through Armenian territory. Nakhijevan also has a crossing point and land connection with Turkey. Thus, the Azerbaijani side’s arguments that Nakhijevan is in a semi-blockaded state and that infrastructure passing through Armenia’s territory is vital for that territory’s connection are an exaggeration. On the other hand, for the Armenian side, connecting with southern Armenia through Nakhijevan territory is much more convenient and faster than through Armenian territory. For example, to reach Meghri from Arax through Nakhijevan territory requires traveling 187 km, which would take about 2.5 hours. The same journey through Armenian territory is 330-350 km long and takes an average of 4-5 hours. For this very reason, the principle of reciprocity related to opening infrastructure is extremely important and justified for the Armenian side.

Besides this, limitation to only the road passing through Meghri (which will have a parallel branch also through Iranian territory) also deprives Nakhijevan of more convenient roads for connecting with the external world. In the future, in case of unblocking all infrastructure, the residents of the Nakhijevan Autonomous Republic can use Armenian territory to connect with neighboring countries in the following directions:

- With central parts of Azerbaijan via the Nakhijevan-Bichaanak-Goris-Stepanakert-Yevlakh road.

- After completion of construction of the Mrav (Murovdag) tunnel, to connect with northern parts of Azerbaijan via roads passing through Armenian territory: Nakhijevan-Sharur—Areni—Selim Pass—Sotk—Mrav tunnel—Ganja.

- The most convenient road connecting Nakhijevan with Georgia and Russia passes through Armenian territory: Nakhijevan-Sharur-Arax-Yerevan-Ijevan-Tbilisi.

- Using Armenian territory’s railways in case of opening the Armenian-Turkish border, it is also possible to carry out the most convenient railway freight and passenger transportation from Nakhijevan (and Iran) to Kars, and then to central Turkey.

On the other hand, as noted, the road passing through Nakhijevan territory is twice as short for reaching southern Armenia (Meghri, Qajaran, Kapan) than through Armenian territory. Opening Nakhijevan’s border will also create direct railway connection for Armenia with Iran via the Julfa junction.

Conclusions

Although the Azerbaijani side notes that the road passing through southern Syunik is vital for connecting with the Nakhijevan Autonomous Republic, it has an alternative variant of this road through Iranian territory, which differs insignificantly from the Meghri road in its length. On the other hand, in case of using all available communications instead of one road, Nakhijevan’s population gets the opportunity to connect with neighboring countries (Georgia, Turkey, Russia) through various sections of Armenian territory via more convenient and shorter routes, as well as with northern and central parts of Azerbaijan. The Armenian side, in turn, as a result of unblocking according to this principle, gets the opportunity to establish faster and more convenient connection through NAR territory with southern settlements of Armenia (Meghri, Kapan, Kajaran), as well as with Iran, through whose territory also with ports of the Indian Ocean.

Samvel Meliksetyan

[1] https://easyzoom.com/imageaccess/ec482e04c2b240d4969c14156bb6836f

[2] https://runivers.ru/bookreader/book57910/#page/149/mode/1up

[3] Hayrenik Magazine, 1930, № 1.

[4] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f0/Map_of_Caucasus_Krai_1903.jpg

[6] https://archive.org/details/B-001-028-311-ALL/B-001-028-311-01/

[7] https://mediamax.am/am/column/121253/

[8] https://archive.org/details/aadsssr1986/DOC/page/n123/mode/2up?view=theater

[9] https://www.aniarc.am/2023/04/04/meghri-1999-long-read-tatul-hakobyan/

[10] https://panarmenian.net/m/eng/news/13465

[11] https://www.aniarc.am/2023/04/07/davit-matevosyan-kapan-meghri-railway/

[12] https://news.day.az/society/1744771.html