Current State of Ideologies and Level of Research

The party system in Armenia continues to remain in a development phase. In one of our previous works[i], we noted that one of the reasons for the inaction and partial functionality of numerous registered parties in Armenia is their weak ideological foundations. Along with and because of the party system’s partial functionality and weak ideological foundations, there are few studies on party ideologies.

From the constitutional law on parties[ii], one can understand that ideological foundations are reflected in a party’s program and charter. The existence of a program and charter is a mandatory condition for party registration. Additionally, one of the three components of state targeted funding for parties was research on party ideology, programmatic goals, and public policy issues (more details about state funding of parties can be found here[iii]). However, very recently, the National Assembly adopted a legislative project making changes to the Electoral Code and related laws. As a result, parties will no longer receive state funding for research on party ideology and programmatic goals. This was justified by the difficulty in validating the existence of research and the overall lesser importance of this research component.

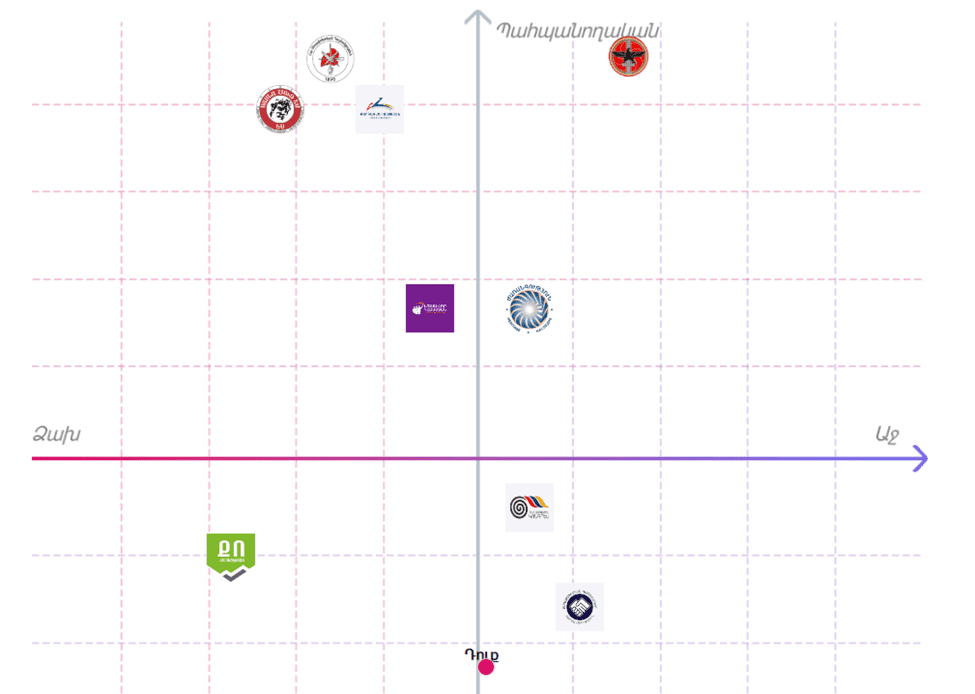

Among the poor sources on parties’ and Armenian society’s political ideological orientation, one can distinguish the “Political Compass[iv],” which, however, has its shortcomings. Through a questionnaire, the Compass tries to reveal the political-ideological affiliation of the respondent and reflect it on a coordinate axis. Additionally, the Compass has decoded certain electoral program provisions of some parties and projected them on the same coordinate axis, making it possible to compare an individual’s political views with party ideologies. Regarding the tool’s substantive and methodological shortcomings, first, due to the absence of an analytical overview and methodological section, it’s unclear which time period the ideology measurements refer to. From the composition of existing parties, one can assume that it refers to 2018. Furthermore, the questionnaire is quite abstract and seems not fully adapted to Armenian realities. A significant portion of questions is relevant in many Western European countries; therefore, using it as a basis to compare results with Armenian parties’ ideologies may create distortions. And finally, which is also noted in the Compass’s analytical sheet, there is no sampling or filter to validate the questionnaire respondent. It’s noted that out of 14,000 respondents, 3,500 are real, but it’s unclear where this conclusion comes from and whether these arbitrary 3,500 respondents filled out the questionnaire only once. Otherwise, we might get a picture of ideological inflation.

At one time, in 2018, there was also the “Entaramat” tool[v], which essentially performed the same function as the Compass but in the context of specific elections. However, it currently doesn’t work, and it’s impossible to use that tool’s data. Nevertheless, in the absence of alternatives, we will accept the Compass data as a partial starting point.

Thus, after completing the questionnaire, several parties in the Armenian political field, using conservative/liberal and left/right variables, according to their programs, were distributed as shown below (Picture 1)[vi]. The Compass also offers an actual picture, where parties are less conservative. However, there is no explanation regarding the measurement of the “actual” plane.

Picture 1: according to party programs

According to this tool, the averaged point of survey respondents is located in the left-liberal sector. Female representatives have more liberal and leftist views, while male respondents are in the same quadrant.

From all this, one might think that if a significant portion of the public holds left-liberal views, then parties should also adapt their ideologies to maximize votes. Or, in other words, the averaged point of parties by clusters should not be far from the averaged point of voters’ political views by clusters. However, we see that parties largely have more conservative ideology, while on the left-right axis, existing ones are relatively equally represented.

Development and Characteristics of Ideologies in Armenia

This picture does not reflect the assertion made at the beginning and previously that Armenia’s party field is poor in ideological diversity and has weak ideological foundations. To substantiate this claim, it’s important to reference the history of party and political system development in Armenia.

The development of party and political ideologies in Armenia is characteristic of the situation in several post-Soviet countries, taking into account the path dependency of newly independent countries on Soviet socio-political institutions.

Thus, nationalism becomes dominant in the political-party ideologies of several newly independent countries, including the three Caucasian republics. As such, nationalism as an ideology was best suited to serve in opposition to communism, emphasizing national and historical characteristics. In the Soviet Union, humanitarian scientific institutions were the centers of nationalism development. Studies of history and language eventually became the axis of political ideologies. Several political leaders (Ter-Petrosyan, Elchibey, Gamsakhurdia) and elites of the newly independent countries were individuals affiliated with these institutions. The escalation of ethnic conflicts in the region contributed to the activation and spread of nationalism. The interaction between the rise of nationalism and ethnic conflicts created a vicious circle, which essentially made nationalism a hegemonic ideology in the political sphere.

Parallel to nationalism, political subjects of independent countries somewhat adopted the values of liberalism. Liberalism was also an effective option for opposing the old regime – communism. In the Caucasian republics, a mixture of liberalism and nationalism in different proportions became dominant. Retrospectively, it can be argued that in countries like Armenia, where liberalism was emphasized more than nationalism, the new regimes had a longer life. At the same time, in the above context, it can be argued that in Armenia in 1998, the ideology of liberalism significantly gave way to nationalism, while in 2018, the opposite occurred.

Besides the liberalism-nationalism ideological plane, the foreign policy plane is important in the political ideological foundations of Armenia and other post-Soviet small countries. The latter is closely related to but not identical with the liberalism-nationalism plane. Foreign policy orientation in Armenia and many other Soviet countries serves as a crucial platform for parties in elections, and in many cases, the liberalism-nationalism identification is implicitly defined and pushed to the background.

In post-Soviet countries, the quality of regimes depended on the balance of power between the old regime – communism – and new subjects. Armenia found itself in an intermediate state, where the old regime was partially adapted and integrated into the new regime, carrying within it dominant nationalist and liberal values. The entire process of ideological development has been accompanied by the dominance of nationalism and, under these conditions, certain manifestations of liberalism. Additionally, parties, when opposing the government, have used left-wing populist platforms, referring to Armenia’s poor socio-economic condition. However, overall, the left-wing ideological spectrum is poorly represented in Armenia’s political system. The situation is worse in the context of the results of forces with left-wing ideological foundations. Only the ARF takes such positions, which, however, has mostly adapted leftism in the context of nationalism.

Conclusion

In summary, it must be reaffirmed that ideological diversity among parties in Armenia is poor and largely relies on nationalism and, to some extent, liberalism. The low prevalence and demand for leftism mainly comes from both resentment towards post-Soviet communism and the inherent social-oriented foundations of post-Soviet states. Parallel to this, the foreign policy direction dilemma is a dominant political ideological agenda. Nevertheless, the field of political ideologies and their application in Armenia remains understudied and needs clear measurements and evidence-based research.

Author: RCSP associate expert Tigran Mughnetsyan

[i] https://rcsp.am/entry/5290/kusakcakan-hamakargi-yndhanur-nkaragiry/

[ii] https://www.arlis.am/documentview.aspx?docid=166242

[iii] https://rcsp.am/entry/5537/hayastanum-kusakcutyunneri-hanrayin-finansavorumy/

[iv] https://political.am/storage/uploads/files/zekuyc/compass.pdf

[v] https://www.facebook.com/entramat.am/?locale=hy_AM

[vi] https://www.instagram.com/political.dialogue/p/CsYi7ljMWqX/?hl=de